Noni Jabavu, the first Black South African woman to publish books of memoir, was also one of the first African women who pursued a literary career. At thirteen, Noni left South Africa to continue her schooling in England, returning only for short visits in the decades that followed. In 1977, she embarked on a biography of her late father, the illustrious politician, educationist and writer, DDT Jabavu. To do her research, she had to return to South Africa. A travelling Black woman of means, with a British passport and loved ones dotted across the globe, Noni was rudely confronted by the indiscriminate cruelty and indignity of apartheid.

In this time, she wrote a series of columns for the Daily Dispatch, sharing her often astonishing daily experiences. These columns, compiled here for the first time, display her sharp intellect, her love for her family and her people as well as the intense alienation she often felt.

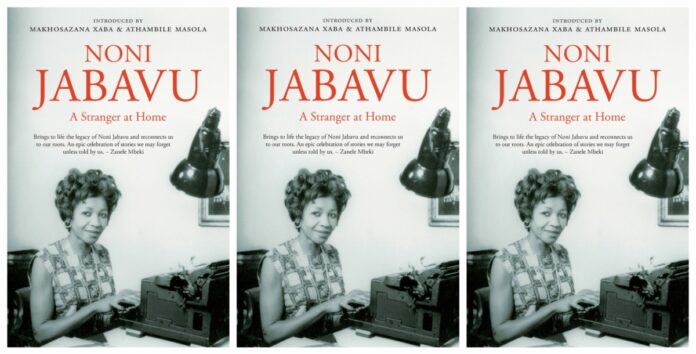

The authors: Helen Nontando (Noni) Jabavu (South African writer and journalist), Makhosazana Xaba (anthologist, essayist, short story writer and poet) and Athambile Masola (writer, researcher, poet and teacher at the University of Cape Town)

An extract from the book has been republished below with permission from the publishers..

9 FEBRUARY 1977

How did you come to be sent to England so young? What did you feel about it?

A house called Tsalta, at Claremont, Cape, was where I first beheld and shook hands with the English couple who were to be my guardians in England. That house was where General and Mrs JC Smuts lived. Its name was backwards for ‘At last’.

Like a typical black child of those days, at thirteen I was not too well primed about the negotiations that must have gone on between my parents and my prospective loco parentis about the life they were planning for me which, I was to learn in years to come, was to be a practical demonstration of the generations of friendship between the families. I learned then that the plan was for me to be trained as a doctor to serve my people. But it misfired, for a medical doctor was the one thing I didn’t want to be. I didn’t know what I wanted to be.

After the boat trip from East London to Cape Town, we were chauffeur-driven to a rambling country-style house at Claremont. The master of the house, umnini mzi, a sprightly old Boer wearing a white goatee and khaki shorts, introduced everyone to everyone. He told me and my little siblings to call him ‘Oom Jannie’, and to call a very fat smiling Boer lady ‘Tante Beebas’ and a small, very curly-headed lady ‘Tant Isie’.

Oom Jannie took my hand and led me to an elderly couple (elderly to my eyes, anyway; I was dismayed to see no children around) and said: ‘And now, Nontando, here are your Uncle Arthur and Aunt Margaret who are taking you to England.’

I was surprised and thought: ‘What, now? But we’ve only just come.’ It was as if Oom Jannie had heard my thoughts because he said: ‘But first, let’s have tea. Then, Margaret, we’ll all go and look again at our pride and joy.’

Jolly old man, he talked non-stop. This to me was natural. At home I was accustomed to the master of our house doing all the talking, cracking jokes, making his captive audience happy. It was the sort of South African household scene I knew.

Tante Beebas took me to sit on a sofa beside her and whispered as I gazed at my new Uncle Arthur and Aunt Margaret: ‘You will like them very much, they are going to be nice to you, so don’t worry – neh? And you won’t be lonely, they’ve got children and young people, only they are out playing tennis with friends this afternoon,’ and she warmly pressed my hand.

She was like the fat Boer ladies at home in our little town Alice, friends of my mother with whom she exchanged teatime visits and endless messages by hand of garden boys – to do with cookery recipes, pot plants and so on. They used to exchange copies of the Farmer’s Weekly and a roneoed sheet of The Egg Circle; women with names such as Botha, Bezuidenhout, Petzer. Our town was a slow-flowing stream of non-racial friendliness and contacts between its resident Boers, English, natives – such names as Taylor, Glass, Burl, Tremeer, Jabavu, Bokwe and so on. Tante Beebas murmured away and, like a well brought-up child,

I kept quiet and listened. Which was just as well, for I was thinking that the one called Tant Isie was a coloured old lady. Again, to me quite in order, for we had coloured friends at home. Mr and Mrs Pease, for instance; their daughter was a great friend of mine.

Later I was to discover that my assessment of the curly-headed lady had been a childish thought indeed, nitwitted, for she was but Oom Jannie’s pure Boer wife . . . But children can entertain the most unpredictable ideas!

When we all rose at Oom Jannie’s bidding to follow him down his garden paths, he lifted my brother on to his shoulders, clasping the little ankles with one hand. And he and Aunt Margaret led the leisurely procession pointing at specimens – the ‘pride and joys’ – among the profusion of shrubs and creeping plants as they went with a walking stick and a folded parasol, talking animatedly. Uncle Arthur, my mother and sister followed, she lifting up her arms to hold both their hands and prattling away unselfconsciously, grown-ups listening with amused attention. Tante Beebas and I brought up the rear, I adjusting my step to hers, slow and stately because of her immense size.

It can’t have been prior arrangement that Tante Beebas explained my new relations to me. Looking back, I imagine she was behaving naturally. Natives used to say that ‘Boers are like us, are people, have humanity – linobuntu iBhulu. They like to communicate, as we do. A Boer can be your father, mother, and beat you, train you (ukuqeqesha) if you disobey his paternal commands. Don’t we beat children, qeqesha them? Spare the rod and spoil the child. And the Boer can be so kind – oh don’t talk about it! Unlike amaNgesi. They have not the warmth of the Boer. So ‘correct’ speaking through those closed lips and teeth, leave the black man to flounder by treating him as a mature creature with brains, stupid as we are – sizizidenge kangaka! No man, the Boer is better, is understandable. You know where you are with a Boer.’

Younger generations of my fellow blacks will be incensed to hear that such opinions were current, but it is fact. That is the kind of ‘identity’ the Boers had for some time before they developed the ‘Afrikaner identity’ of Dominee Vorster.

So, in 1933 Tante Beebas was behaving like ‘a proper Boer’ old lady, treating me as my mother would, had she not been busy discussing things with my new uncle. Black and Boer society in those days had, sociologically speaking, mores that were not dissimilar. As her explanations drew to a close (for the party was now ambling back to the verandah), a chauffeur-driven limousine was waiting to bear us Jabavus to Newlands, where we stayed until my family sailed back to East London, leaving me suddenly disconsolate.

Tante Beebas said comfortingly that she and the Oubaas were coming to England that summer – in a few weeks – and she’d come and see me again. ‘And I’ll find you happy like I’ve told you, promise?’

In England the following month sprightly Oom Jannie appeared on the scene. It was during the ‘hols’. His arrival coincided with my fourteenth birthday, and I was bombarded with gaily wrapped presents from each member of my families – at home in England.

We had gone to our country cottage in Berkshire, botanising, birdwatching. At the cottage – at Aston Upthorpe – the idea was that we ‘roughed’ it as a health-giving change from Chippendale settees, mahogany dining tables. We went in two cars accompanied by our uniformed servants. They were put up comfortably in the village pubs. All of us slept in sleeping bags on the brick-flagged entrance hall which became a dormitory. Oom Jannie, next to him me, then Aunt Margaret, my ‘sister’ Helen, brother Nicholas, Uncle Arthur, and brother Anthony.

Next morning when Oom Jannie espied the birthday present-giving, he dashed upstairs to the room that was his rough workroom (he was making political speeches in Europe on this visit) and dashed down bearing a gift for me. He dropped on his haunches, beckoned me to him holding a little book, opened the flyleaf and inscribed: ‘For dear Nontando on her 14th birthday J.C. Smuts.’

Published by Tafelberg Publishers, the book is available online and at all good bookstores.