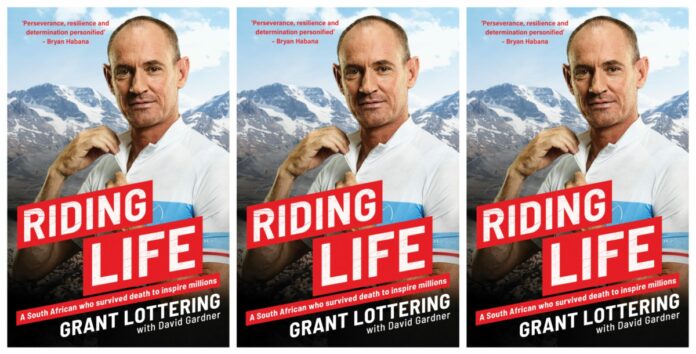

He was told he would never cycle again. But South African ultra-endurance cyclist Grant Lottering doesn’t take no for an answer. In 2013, Lottering’s heart stopped after a gruesome accident in the Italian Alps. Doctors said he would never ride again. Since then, he has completed many gruelling rides through some of the toughest terrain on the planet. Grant Lottering is a highly regarded motivational speaker and ambassador for Laureus Sport for Good. His story – proving that the human body can achieve the near impossible if you have the right mindset – is an inspiration to millions.

An extract has been republished below with permission from the publishers. The book is published by NB Publishers and is available at all good bookstores and online.

The crash

21 July 2013: Trento, Italy

The speed of the start took my breath away. Flying through the cobbled streets, desperate to keep up with the leaders, I gripped my handlebars for dear life. The tiniest of margins – a slip of my 23 mm tires, a corner taken too tight, the slightest of clips to the wheel in front – was all the difference between triumph and tragedy. It was out of control, terrifying, nerve-shredding . . . and absolutely intoxicating.

Moments earlier, I’d been standing with my bike, chatting in the early-morning sunshine with the other cyclists in Trento’s idyllic Piazza Duomo, sharing our relief that the overnight rain had spluttered out. Couples wandered arm in arm past Neptune’s Fountain and I looked up in awe at the Wheel of Fortune Rose Window, a stained-glass window calling me to account from the Cathedral of San Vigilio. My red number 744 pinned onto my blue and white vest signified I had been placed in the fastest group of the 140 km race through the Italian Alps, a pole position I was proud of until my butterflies on the starting line became pure terror. This was the moment I trained so hard for. Twelve months of total commitment and dedication to get here in the shape of my life: a lean, strong 69 kg, 44 years old, my resting heart rate a comfortable 41.

I had trained with a high-performance sports centre at a major South African university; I had a nutritionist, a physio and my friend Justin Erasmus, who’d taken me motor pacing behind a scooter for 50 km after I’d already cycled 100 km. I was super fit, super strong, super confident. Nothing but keeping pace with the wheel in front mattered. Maybe it was a metaphor for my life, maybe not, but I was not going to allow myself to drop back into the peloton of also-rans. I was determined to win my age category. I just didn’t expect the start to be that fast. The friendly banter was over the second the chequered flag dropped, and a stream of grim-faced riders flooded out of the historic old town towards the verdant lakes and vineyards of the Valle dei Laghi towards Monte Bondone ski resort, the finish line at the summit of a 21 km climb. It’s a stunningly beautiful, iconic ride intersecting fields and fields of Chardonnay grape. Not that I noticed much – I was too focused on staying upright. For 10 km through the Trento suburbs, we were riding so fast we were bunny hopping over roundabouts rather than going around them.

Nobody was giving an inch and I was right there in sight of the leading riders. I’ve watched YouTube videos of my race and others to see smiling riders giving thumbs up and chatting as they cycle in groups past the lakes. But my experience on 21 July 2013 was nothing like that. I was being pushed along by a hurricane of hopes, dreams and thwarted ambition.

Taking no prisoners, full on – or ‘full gas’ in cycling speak – the entire way. The competitive nature that had quietly defined my entire life exploded to push me to the very limit and, I couldn’t help thinking, a little beyond. The pace was unrelenting, unlike anything I had ever experienced, even in my younger days as a professional cyclist. The intervening years, when my path had led away from my dreams, slipped into the past as I focused on the road ahead to see the race squeeze into a single lane climbing up through the green vines clinging to the hillsides. My heart rate was off the charts. My legs felt heavy, swollen by lactic acid. I’m usually a good climber and expected to have time to feel my way into the race and gradually step up the power, but it was full gas from the start. I never expected the racing to be so violent. I could see a village at the top of the climb and knew I was just 100 m behind the lead group. Head down, push, push, push, legs burning, lungs bursting. This is racing, Grant, I said to myself.

This is racing. Into the tiny Alpine village of Palù del Fersina, home of legendary Italian cyclist Gilberto Simoni, who won the Giro d’Italia twice, in 2001 and 2003. The tarmac gave way to cobbles, the street a car’s width and no more. Then it was up and over the peak like a bat out of hell, a lemming over a cliff. A leap of faith.The blinding sun made it almost impossible to pick a line. The villagers were a blur as they cheered and stepped back to evade the waterfall of rainbow jerseys pouring through their streets. Relief as we left the narrow lane behind for the tarmac that snaked down the mountain for 9 km, leaving the crowds in our slipstream. Some sections of the road had dried out in the sun, but some patches were still wet. It was hard to read, and I couldn’t escape the feeling that I was out of my depth, but there was no time to process the thought. Every brain cell, every muscle, was devoted to fighting for position and keeping me in touch with the leaders. I was in a group of seven or eight guys – the elite –coming into the Valle di Cembra, the Dolomites towering high above us. A road sign came into sharp focus through the noise and excitement: a blazing red 17 per cent gradient caution sign.

I hung on. I glanced down at my bike computer: my speed was 66 km/h on the twisting, zigzag road. Looking back up, I saw the left-hander coming fast. Too fast. Wrong line, Grant. I saw some water on the right and a drainage ditch coming for me head-on. Suddenly everything slowed down. I was going to crash, there was no doubt, and I could see it unfolding as if I were watching it in slow motion on TV. The bike twitched when it hit the water and went straight. I managed somehow to bunny-hop the ditch and for a split second I thought it wouldn’t be too bad. The end of my race, certainly, but with little more than bumps and scratches and a bruised ego. Then I saw the embankment. Don’t hit your head! was my last thought before I slammed into the rock like a sledgehammer. That was the moment, right then, when everything changed. The end of my first life.

The shattering impact when I hit the rock embankment 45 minutes into the race should have been fatal and final. The fact that I turned my head at the very last second saved my life for sure. My helmet wasn’t even scratched but the force of the collision had a devastating effect on my body. I didn’t know the extent of the damage at the time. I couldn’t even tell where it was because the pain was so excruciating. I remember crying out in agony, blood spraying out of my mouth and into the concrete ditch next to my head where I lay in the foetal position facing the oncoming cyclists, my lower body and legs on the tarmac. I didn’t lose consciousness, which was maybe both a blessing and a curse. I was aware of everything that was happening to me and I truly believed that it was the end. I remember screaming for help but could not inhale air back into my lungs. There was blood everywhere and I couldn’t move. Then another competitor came around the corner, crashing straight into me, snapping my femur in half. It’s one of the hardest bones to break, but it was sticking right out of my skin. By now, my screams of pain had turned into cries for help: I could not get air into my lungs and blood was still spurting from my mouth with every shout. Luckily, the other rider wasn’t badly hurt. Even luckier, he turned out to be a doctor and he stayed with me. I was losing so much blood. At some point in this terrifying chaos, another cyclist stopped to help. His name was Uli Fluhme, from New York, a cycling race organiser and experienced cyclist.

Together, they did what they could to help. Uli told me later that he’d had to keep his hands on the severed arteries in my neck and right arm to try to stop the bleeding. I can vaguely remember his American accent trying to calm me down. But I absolutely knew I was going to die.