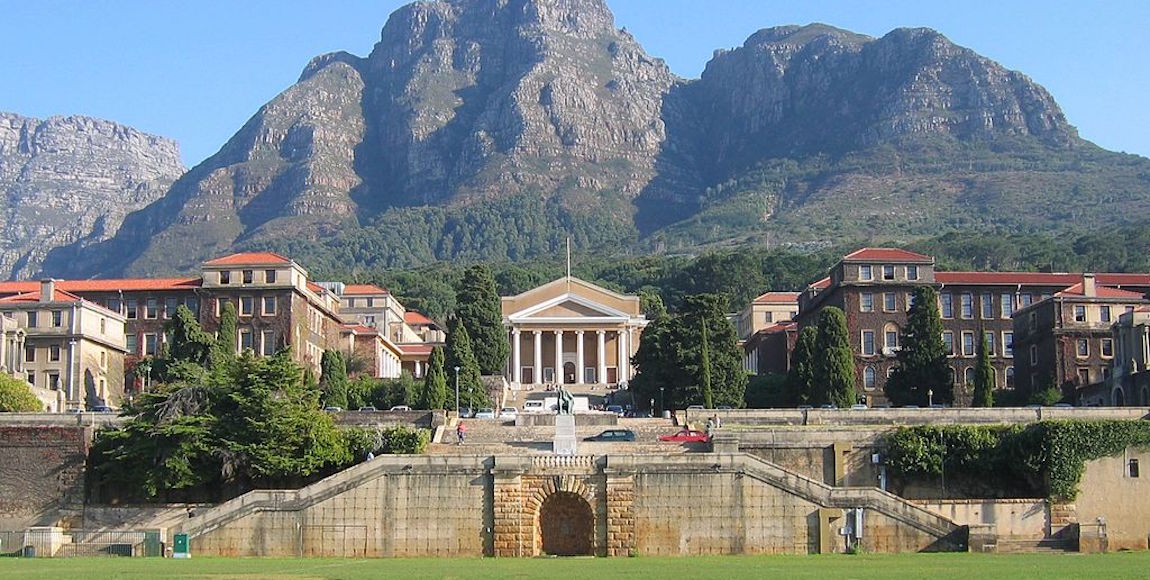

On Wednesday, 8 August, the University of Cape Town’s Faculty of Humanities presented the inaugural Archie Mafeje Memorial Lecture, by Professor Shahid Vawda. Vawda holds the Archie Mafeje Chair in critical and decolonial humanities, as well as the directorship of the School of African and Gender Studies, Anthropology and Linguistics. In his lecture, he outlined how we can honour the legacy of Mafeje and how his recently-assembled research group plans to use Mafeje’s work as a launching point for their own studies of the history and social formations in Southern Africa and, more specifically, the Southern Indian Ocean.

The vice-chancellor Mamokgethi Phakeng and deputy vice-chancellor for transformation Loretta Ferris were in attendance, which gave the occasion a certain gravitas. There was also an element of poetry to the evening, as it coincided with the 50th anniversary of Archie Mafeje’s historic nine-day occupation of Bremner Building, which was the result of UCT rescinding its appointment of Mafeje as a senior lecturer in social anthropology after pressure from the apartheid government. Vawda eloquently illustrated how the late thinker’s ideas have never been more relevant and pertinent in our local context. “It is the idea of the primacy of Afrocentrism and decolonisation – in truth, the positionality of researchers and their research,” he said.

But UCT’s ivy-laden buildings and institutional culture gives rise to skepticism about what the Archie Mafeje chair may accomplish at the university and, more importantly, questioning why this has emerged now. However, Professor Harry Garuba allayed these concerns by expounding upon the origins of the Chair and its deep-rooted sincerity in Professor Vawda emphasis of Afrocentrism and decolonisation. “The period in which we put in the application to establish the chair was a period of great unease, both intellectually and socially, across campuses in the country and the great call was on the decolonisation of education and the decolonisation of universities […] We thought we could ride on the coattails of this cause and establish something permanent in the Humanities Faculty to take the kind of scholarship that takes this seriously forward,” he said. Finalising funding, Garuba intimated, was what caused the Chair to only be officiated in 2018, three years after the historic #RhodesMustFall protests he alluded to.

Vawda made a concerted effort to speak intimately on Mafeje’s seminal work, The Theory and Ethnography of Social Formations. “The major part of his book is a debate about the use and value of Eurocentric or ethnocentric concepts, such as those drawn from Marxist frameworks, like class or caste and feudalism. In the book he seeks to empirically draft what [interlacustrine] kingdoms are like and question whether these kingdoms have state-like feudal structures and are susceptible to class analysis or class struggle,” Vawda said. He emphasised that many of the foundational lenses that academics, researchers and social thinkers are intrinsically European, particularly those that speak to the proletariat and broader working class. Literature that has provided frameworks for castes, classes, feudal structures and social stratas, however noble their intentions, all have their roots in Europe. Any attempt to mould these ways of thinking and superimpose them onto Africa in order to better understand them is, for Vawda, one of the critical failings of academia in the global South.

The Mafeje Chair’s key vision is to focus on Africa, the post-colonial world, the global South and its role in the making and unmaking of disciplinary knowledges and practices. Varda emphasised that his research group will focus on the Southern Indian Ocean region but that there are still numerous spaces, people, histories and entry-points through which to create truly Afrocentric forms of knowledge reproduction. At the core of Southern Africa’s ills, the potential solutions and ways forward are Eurocentric ideas that Mafeje continued to challenge in his writing. The crux of it all being that Africa cannot use the basis of European reality and the solutions thereof to address its own realities – particularly redistributive economies. “Mafeje pointed out, firstly, redistributive economies are a concept of Western economists. It follows Weber and Polanyi and considers [redistributive economies] to be marketless, stagnant and non-innovative. Any passing acquaintance by rural areas in South Africa will confirm that this is nonsense. […] Rural populations are very complex. They are no less complex that urban. They range from king-based descent groups, lineages, clans, small-scale producers, cash croppers, subsistence farmers and rural elites, none of whom are migrant workers who could be defined as classical “proletariat” in the European sense,” said Vawda. It is with thorough, original research that this cycle of Eurocentrism over Afrocentrism will end. With this framework and launching point of wanting to understand Africa as Africans and on African terms, Vawda posed the question that Mafeje ahd grappled with too: is there an African modernity?

What lessons can be learnt from South America, the continent across the Atlantic that also was decimated by colonialism, as Africa was, in understanding an endogenous modernity? “For most [Latin American scholars],” Vawda said, “their conception of modernity starts with the arrival of Columbus, or more directly Cortez’s conquests. For us in the southern tip of Africa, indeed for the rest of the continent, modernity has marched somewhat unevenly with historical developments in Europe and Asia. My colleagues in Maputo and Antananarivo push back the starting date somewhat to about the 2nd century AD. For others it begins with the arrival of Arab traders on the coattails of Islam and, intriguingly, music from the 7th century. For others it might be Great Zimbabwe or Mapungubwe and yet for others it might be the kingdoms that Mafeje analysed in Central Africa. Suffice to say, it is a project that assumes no fixed date, no stages of development, evolutionary or fixed historical starting or end points.” And so, is it for an African modernity to be found, hidden away from us by centuries of exploitation, or will we create our own from the trails of our past? These were questions that were subtly posed and never fully answered – no doubt the hard work his research group will address.

Professor Shahid Vawda’s central theme throughout the lecture was to stress that we, as Africans, do not truly know ourselves and the means of understanding we’ve used have pulled the wool over our eyes. We cannot move forward with conviction without a knowledge of our historical and current selves, which has the capacity to take on an ethereal element that can transcend the exclusivity of academia.

Featured image via Wikimedia Commons