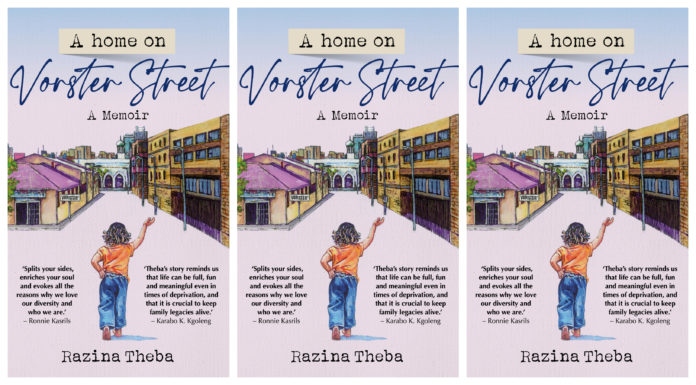

In A Home on Vorster Street, Razina Theba witnesses the ebb and flow of a tight-knit neighbourhood trying to survive the forces of apartheid. Ultimately, it is there where she learns of the value of family love and the enduring comfort it provides. At times funny and charming and, at others, painful and tender, this dazzling collection of stories is a spirited exploration of a colourful Indian-Muslim family bound by loyalty to their culture, community, religion and each other.

An extract from the book has been republished below with permission from Jonathan Ball Publishers.

I remember my first day of school well. The week before was spent filling the expensive stationery list, and I have one of those mums who relished covering the books in fancy wrapping-paper and using Letraset to transfer my name onto the books instead of labels. She shopped for glitter and stickers and bought the more expensive markers that contained more than just the primary colours. The first page of every book displayed an elaborate drawing of a flower. Covering books was a family affair, undertaken in one sitting one night after supper. My dad cut the wrapping to size, dozens of sheets, and then did the same with the plastic. On the edge of our dining room table, identical strips of sticky tape lay in a row waiting patiently to be the final steps in the factory of school preparedness.

A few times, my older sister leaned against the table, grazing the strips and sticking them all down onto the table – that set us back at least half-an-hour each time. Radio Truro crackled out some Bollywood tune in the kitchen and my mum boiled mint tea and absolutely relished the task that lay ahead. Once the books were covered, there was a final check of the pencil-case, and then finally, my first school suitcase leaned against my bed in quiet expectation of Grade 1. It was a hard, brown suitcase with a handle and briefcase style locks that one could flick open. It made me feel very grown up.

After the obligatory first-day-of-school photo of me leaning against the smartest car in the street, hand on my hip and clip holding the fringe out of my eyes, with a school dress at least two sizes too big, I sat down at my desk, face shiny with excitement. Strangely, I do not recall anybody crying from separation anxiety. We were a brave lot, the class of Grade 1s in 1982 at Bree Street Primary School. It would be years later that the word “humiliation” would crop up in the spelling list and we would have to copy out the meaning from the dictionary and know that Grade 1 had a name all of its own.

Mrs Devar, our Grade 1 teacher, was a hulk of a woman. She arrived unsmiling with her hair pulled back in a tight bun revealing a self-inflicted diminishing hairline and an orange sari. The sari is a beautiful garment. It dances with its wearer: it is like an echo in a love song, the flicker of a fighter fish’s trailing tail. That Mrs Devar, with her crude disposition, wore a sari was a travesty – there was nothing fluid or soft about her. By June 1982, I hated the sari almost as much as I hated her. It was her uniform. During winter, she teamed it up with a beige knitted cardigan. The black Green Cross sandals were also a permanent fixture. In summer when she wore no socks I spent a fair amount of time following the progression of the fungal infection in the big toe of her right foot.

“Who can write their name?” she barked after roll call on the first day.

I put my hand up and was horrified to see that I was the only one. I had obviously not read the atmosphere accurately. I knew that Sameera Khota could write her name, I saw her do it, why was I the only one volunteering this information? Surely it was a good thing? Mrs Devar signalled for me to take the chalk and pointed at the blackboard. Hesitantly, I wrote my name on the blackboard. I remembered the capital letters and tried to get the small letters in a neat row, painfully aware of 28 sets of eyes staring at me. The chalk squeaked disturbingly as I heard my mum’s voice in my head, “The ‘a’ is round, up and down … the ‘z’ is easy, just two lines and then join them …”

“Razina?”

“Yes, Madam.”

“Did your mother buy you the ruler that we asked for?”

“Yes, Madam.”

“Bring it here.”

I was relieved. I would line up the ruler under my name. I knew the word: underline.

“Hold your hands out. Knuckles up.”

The white Penguin ruler bore down on my hands at a 90-degree angle.

Primary school was strange. We had a teacher who hung a naked Barbie doll on the edge of the blackboard and occasionally spoke to her. His eyesight was poor, he wore thick black-rimmed glasses and he positioned his body close to the board, legs apart and bent. By Standard 5, the boys in the class took to biting off bits of paper, chewing them into a masticated mass, loading it into a straw and spitting it onto the board while he was writing. Mr Chagan would identify this as an imperfection on the worn-out board and continue to write, going around the disgusting spitball. Occasionally, a ball would land on his back or in his hair and sit there for the rest of the day. Whichever boy achieved that feat would be elevated to hero status until second break. Mr Chagan was oblivious to questions, comments, good or bad behaviour. It was as though the bell signalling the end of one period and the start of another just meant for him to rinse and repeat. He asked for no respect from his learners and we, in turn, gave him none. I sometimes wondered whether our treatment of him was humiliating, or if he was unaware of it. His humiliation sat in quiet silence in a spit ball on the nape of his neck.

The Group Areas Act denied our parents any options in terms of picking a high school and so my friends and I went to Johannesburg Secondary School, a block away from the primary school, in 1989. The buildings were disintegrating and the fields were sand. A soccer match raised a dusty storm which, mixed with perspiration, made the boys it landed on look as though they had been in an earthquake. There were 1000 pupils crammed into a space designed for 400. The school hall was divided into five classrooms and one could tune in to any subject being taught in that space.

By this time, many families of Indian origin had relocated from Fordsburg and Newtown to the neighbouring areas of Mayfair and Homestead Park. The whites-only high school in Homestead Park was a three-storey face-brick work of art that could comfortably house 2000 pupils, but it served 15 white pupils. It had three grassed soccer fields, a fully equipped laboratory and massive, airy classrooms. There were red velvet stage curtains in the school hall, a sound system with theatre lighting and electronic printing equipment. This changed in 1990, when schools were forced to become racially integrated. As a community immersed in the political atmosphere of the day, we collectively and defiantly left behind the Roneo duplicating machines of Fordsburg and occupied the space, electronic printers included, in Homestead Park. By the time we settled down, all but four of the school’s previous learners had left. The location had changed but we brought with us the name “Johannesburg Secondary School”.

My peers and I were juniors in the new environment. We were 13 years old, battling unstable hormones, pimples and puberty, and had survived many years of humiliation at the hands of teachers in primary school. Some had worn the label “troublemaker” with pride. This group arrived at high school with a dik attitude. I, on the other hand, had learnt at primary school that if I shut up, did my work and just got on with things, I would have a different experience from the ones who were always being marched off to the head’s office. I quietly watched the teachers, reading body language, knowing when to answer and when not to. It was manipulative and insincere, but it had earned me Head Girl status in Standard 5.

Johannesburg Secondary School had a reputation for drugs, fistfights and incompetent teaching. Principals had come and gone within months of each other and on my first day it was easy to see why. Orientation week assembly with the new principal went something like like this:

“OK, so I want to welcome all the new rubbishes from primary school. Don’t think that you can come here with a dik attitude. We won’t tolerate that. If you want to behave like the rubbishes in the higher grades, you will see what we will do with you. This year I am focusing on DISCIPLINE. I’m going to turn things around. I don’t take shit from pupils …”

He lost me after the second time he called us “rubbishes”. It was going to be more of the same.

Still, I was optimistic. The plan was to just get through this. Feign respect, comply and I thought I would be fine.

The book is available now through all good bookstores as well as Loot and Takealot.