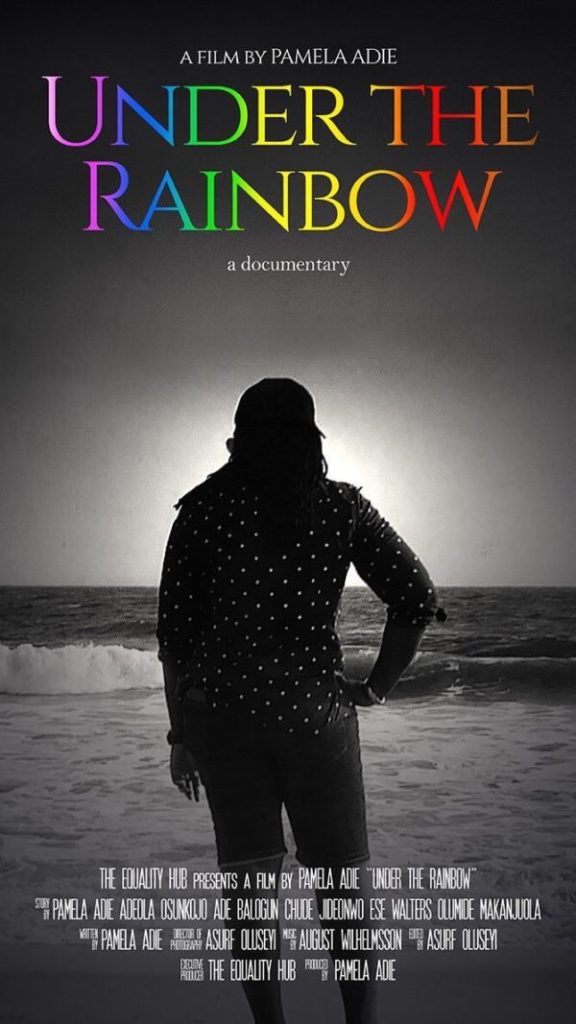

Queer Nigerians exist and are as complex and human as everybody else. This is the message behind Pamela Adie’s documentary ‘Under The Rainbow’. The film — written, produced and directed by Adie — tells her story as a Nigerian lesbian living openly in a society beset with homophobia. The Initiative For Equal Rights and members of The Equality Hub, of which Adie is the executive director, backed the film in Nigeria. Various South African civil society organisations backed it too. The film diversifies common narratives and uses storytelling as an advocacy tool to tell the story of queer people in Nigeria in all their diversity and glory. The Daily Vox caught up with Adie to chat about her film.

What prompted you to make the film ‘Under The Rainbow?’

When I was contemplating coming out, I was looking for role models: people who I could look up to and who I could draw inspiration from. But I didn’t really find a lot of people from Nigeria that looked like me. I wanted them to be able to look back and see that someone that looks like them, in their country, actually can come out and live a happy, and fulfilling life.

I wanted to put a human face to the story of what it means to be lesbian in Nigeria because too often we see over narratives that don’t really portray us as people, as human beings, who are full in their wellness.

What kinds of misconceptions about queerness, or at least being lesbian, were you hoping to dispel with your film?

Lesbians usually get portrayed as sex objects, women who are there for the pleasure of men. I wanted the narrative to say, ‘No, that is not accurate. We are all human beings like everybody else. We have family, we have friends, we have fears, we have triumphs’.

This notion of saying that LGBT people don’t exist in Nigeria, that it’s just some kind of foreign concept or foreign idea. I really wanted to debunk that theory, to say that’s not accurate and also to say, ‘We are African, we are Nigerians, we didn’t learn queerness. Homophobia is a foreign concept because its largely sponsored by evangelicals from the West.’

In the movement in Nigeria, gay men are usually more centered through HIV/AIDS prevention programmes. There really hasn’t been a lot of focus on lesbian, bisexual, queer and trans community, even the intersex community. I just wanted to shed more light on the lesbian part of it and give us a little more visibility.

How did you experience making the film? Was it difficult to put yourself and your story in it?

This was really a labour of love. Storytelling has the power to change hearts and minds, to change perceptions about the way people view queer people who look like me across the world, and especially on our continent.

Writing it was was pretty easy, because I’ve written about this multiple times, so it just came naturally. I struggled with speaking about it and got really emotional at some points, especially when speaking about the relationship with my family. When I came out, I was faced with a lot of rejection, especially from my family. Talking about that made me quite emotional and you can see it in the film, when it gets to that point I was really struggling to fight back tears.

But I really feel that people need to hear these stories, no matter how difficult they are. It’s always going to inspire someone out there. Anytime someone comes to me after watching the film or even hearing story and says, ‘You gave me strength to come out’, that makes a big difference.

Who did you make the film for?

I made the film for for young people. There are two audiences. I made the film for the next generation, and also for people who are here now, to help to shift the narrative. I’m not oblivious to the fact that people who are a little bit older might be set in their ways, and might not be able to engage with new information that challenges their notions of how the world works. But I also made the film for anybody who cares to see it.

What is it like to be a lesbian/ generally a queer person in Nigeria?

People are more courageous behind the keyboard than they are when they see you in person. They say a lot of things online, but when you meet them in person they want to take pictures. That’s been my experience. Nobody’s ever come up to me to say, ‘Why are you doing this?’ But I also know that other people are not living with the privileges I am living with and do suffer some sense of homophobia.

I know people who have lost their jobs because their boss found out they were lesbian, I know people who have been kicked out of their homes because they came out of the closet. When I came out, my mom asked me to pack my things and leave the house. I was almost homeless until my dad said, ‘No, you can’t go anywhere’. There are people who aren’t so lucky, who lose their homes, who get [ostracised by] family, go through depression. There’s a big mental health issue happening in Nigeria.

We get bombarded by religious leaders. The church and the mosque pose a really big challenge because they’re out there saying, ‘It’s a sin’. This notion that we need to hate the sin but love the sinner clearly isn’t helpful. How do you separate someone from their sexual orientation?

There’s social exclusion. People do not feel safe enough to come out, or to be honest about their sexual experiences when it comes to health. There’s a lot of focus on gay men and HIV AIDS, but there aren’t a lot of programmes that provide health services for LBQT women. Funding is limited. If we were to get more funding, then a lot of things will become more clearer. One of the key things that we need that’s really lacking is data. There’s so much data about gay men and their experiences out there, but there’s very little about other sexual orientations.

The challenges are enormous, but we just have to keep going and doing everything we can.

Nigeria has some of the harshest laws against LGBTQ persons, what has the reception to the documentary been like so far?

The reception has been great. One of the things that really stands out for me during this screening is how people feel safe to be able to open up and to be able to talk about themselves in ways that they might not otherwise have a chance to do. After the screenings in Nigeria people didn’t want to go home, they wanted to stay and talk. It’s creating that safe space.

This past weekend when the film showed in Johannesburg, there was a lady who said that she had seen that I have been married before to a man. When she saw that this film was out and I was sharing my story, she couldn’t miss it for the world. She had been through a similar experience. She said seeing the film and being there helped her to affirm her own identity, her life, her struggles, her triumphs and to know she’s not alone.

There was another Nigerian guy who said he used to live in Nigeria and was one of the people who believed that being LGBT was some kind of witchcraft. But when he moved to South Africa, his views changed. He saw things will be more differently, and he thanked me for doing this because he understood where I was coming from. The reception has been very affirming.

What are your hopes for queer rights in Nigeria and around the world?

I hope to see a Nigeria where laws protect LGBT people from discrimination of all kinds: social legal, political, economic. We started working towards that. I have a case in court right now where the government refused to register my organisation because it has the word “lesbian” in it. They said it’s offensive and contrary to public policy as reason given for denial. We went to the High Court and the High Court sided with the government agency. The Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act was signed into law by President Goodluck Jonathan in 2014. There’s a section in that law that prohibits the registration of “gay organisations”. It says you can go to jail for 10 years if you register such an organisation. The Court said refusing to register my organisation violates my freedom of association but until this law exists it will not slide in my favour. Now the case is in the Appeal Court in Nigeria.

One of the things we’re asking the Appeal Court to do is to determine the constitutionality of that section of the law which prohibits the registration of “gay organisations”. We’re saying this section directly affects my right to freedom of association. This has big repercussions. If we win this case then it means LGBT rights organisations will be free to register as they are without having to coin names that hide the work that they do. It also means that that section of the law will be struck down. The strategy that we’re using is to attack sections of this law instead of going at the whole thing at once.

But in general I really hope that we see a Nigeria, and a world, that is more inclusive of LGBT people. When I say inclusive, I mean socially inclusive and accepting.

Watch the teaser trailer of the film here.

‘Under The Rainbow’ premiered at a private event in Lagos in June and was since screened other parts of Nigeria, Ghana, and South Africa. There are plans to host the film on a website in the new year. Follow the film’s Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook pages for news about future screenings.