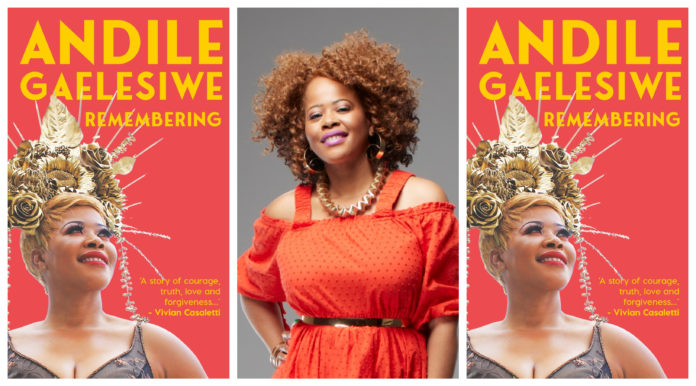

Andile Gaelesiwe is celebrated across South Africa as the adored host of Khumbul’ ekhaya on SABC 1. Yet few know that behind the glamour of her public image, there is a vulnerable girl from Meadowlands, Soweto. Andile grew up in a time of turmoil, not only in South Africa, but also in her family. This led her to look for her biological father who then betrayed her in the worst possible way. In the late 1990s Andile took the music industry by storm when her first single ‘Abuti Yo’ was released. Remembering is Andile’s fierce, and at times funny, memoir. It touches on serious issues of rape and patriarchy, but also reveals a woman with a will of steel, music in her soul, and a commitment to living to the full. Andile’s story is deeply inspirational. (An extract is published below)

Remembering Twelve

‘Abuti Yo’ – my 1996 hit song

– siyabangena

Hearing myself on the radio for the very first time was very weird. It was surreal. It was scary. Scary because I had not shared with family that I was recording this album and izophuma – it would be released. I had not told them about my recording deal.

I remember one of my songs played on Metro and my mother heard it. That is when I got into trouble. My mom commented, ‘Kukhona ingoma eso la emsakazweni’ – there is a song on the radio.

And I said, ‘Yho, that’s not me.’

Remember, my mother never wanted me to sing. But if I did, she would rather have had me singing gospel. Also, in my mother’s mind, music was not a stable career. She did not think it was a livelihood that would sustain me, especially as she was convinced most artists died poor. She wanted me to have what she regarded as a professional career – to be a doctor or something like that.

My mom tried everything to find me a job. She used the job placement agency then known as Kelly Girl. I would work in a job for three to six months and then resign, resulting in a very erratic work profile. All I wanted to do was sing.

I worked at a couple of call centres, including Transtel Cellular. The people I worked with there will tell you how disruptive I was because I was always singing. Shortly after starting at Spoornet HR, when I went out one lunchtime I left the office keys behind and never returned. My mother did not know that I had vowed to myself that I would never do a nine-to-five job. She was not happy about my behaviour.

It was only once I had a stable job at YFM that she started supporting my career: when she attended a function for women executives, she discovered that Andile Gaelesiwe was the programme director. On this day she realised I was good at public speaking.

I understood later that the reason she had not wanted me to sing was that she did not want her child to go through what she had experienced. Being a young woman in the entertainment industry means that people are always going to ask you for sexual favours. And these are things she does not like talking about now. But I remember her saying the industry igcwele amadoda – is full of men and all they do bayakushela – they try to ask you out. As a girl child she did not want me to be in this industry because of those things.

A respected church member’s daughter sang Abuti Yo Ontshwara Hamonate! People were shocked. The church did not appreciate that. That is also why my mom did not approve – because of the spiritual background I had come from. The church must have thought I was now ‘working for the devil’!

We recorded my first album in about three weeks and I wrote all the tracks myself. That’s the thing about music: you collect your first album throughout your life. I was naive and did not know much about the industry, so when I signed a recording deal with Gallo, I accepted only an eight per cent royalty. To this day they still owe me money for publishing.

We shot a video for ‘Abuti Yo’, I started performing and became popular all over the country. There was a lot of hype about me from the beginning; there were even stories that I had had breast implants.

It was an amazing time for me. I was coming of age and coming out. I had been this girl who was always dressed like a nun, covering my whole body. My dresses always came below my knees and my breasts were always completely covered. But when the first album came out I was told that I needed a distinct look and image.

Those were the times of Boom Shaka, and two of the band members, Lebo and Thembi, had long braids that I liked. But I was told I could not have braids because I needed to be different. So I decided to remove the braids and dye my hair – that’s how my journey of colouring my hair began. I dyed my own hair and I liked the fact that I could mix any colours that I fancied. I also wanted to develop my own style, using international artists as a reference.

The ‘in thing’ those days was to wear a short skirt with long boots. That was the look: Sharon Dee, Abashante . . . I looked at Anita Baker’s short hair and dyed my own.

I was given a budget for a new wardrobe and I was told to be sexy. So, for the cover of Abuti I was in a black leopard two-piece pleather short outfit. And long black boots. That was the image I came up with.

The process was fascinating for me because I turned into a whole new person. Andile was born. I started doing radio interviews, I was doing performances and suddenly I had all these men asking me out. At one point, half of the Metro FM DJs were asking me out.

It was a very rapid transformation from the nerdy girl I had been while growing up. And then, overnight, I was the ‘it’ girl.

At live performances, I remember coming off stage and watching artists such as Lucky Dube, Brenda Fassie, or Jabu Khanyile. That’s when, as a new artist, I was among those booked to perform before the big names at a festival. The stadium would be packed and we would open for the legends. While we used backing tracks, when they came on it was a proper sound check with three guitars, a drummer, ten pianos – a full band.

I remember watching this and thinking: one day, I want to have the whole range – from young people to abantu abadala (adults) – appreciating me and loving what I do. At the time, I wanted to achieve that with music. But what I was singing appealed only to young people, although what I really wanted was to reach a wide group – just as Judith Sephuma did.

God had other plans for me. I was later to quit the music industry and do something else that would allow me to achieve what I had wanted to with music.

Out of the blue, I was getting calls for interviews; I think I performed on every show there was on TV. The whole country was happy, except my mother. She had tried and failed to protect me from my father; now she wanted to protect me from the music industry and her biggest fear was that she was failing again.

This extract has been published with permission from Tafelberg.