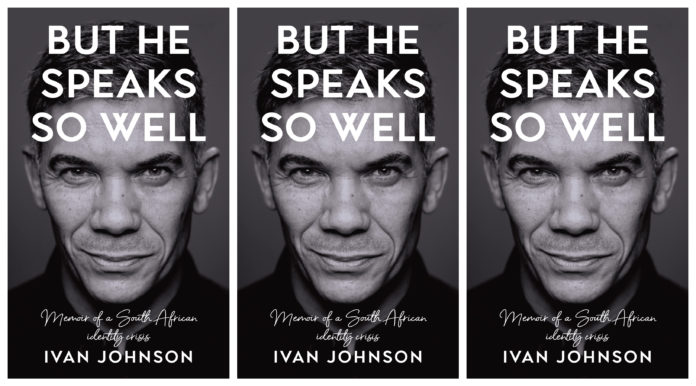

Journey with Ivan Johnson in this memoir of an identity crisis as the highspirited boy from a close-knit family on the Cape Flats comes of age amid the turmoil of ‘The Struggle’. Joining the lily-white advertising industry, he ghosts from group to group, fitting in everywhere but belonging nowhere. Told with flair and irreverence, Ivan’s sharp eye and zest for life offers both food for thought and great entertainment. An extract from the book is published below.

The year 1992 invited us in and so did the world of cricket. South Africa was invited to its first Cricket World Cup in Australia and New Zealand. The full-colour spectacle was beamed through live on our television sets. The newly embraced team lacked colour but for the inclusion of beyond-his-best 40-year-old Omar Henry. Our country’s excitement at the inclusion and participation in cricket far outweighed the inevitable participation of the majority in future elections.

But it was the beginning of a journey and all cheered on with optimism. At the agency, the boardroom’s massive television was commandeered and brought to the creative department. Acts of such disobedience warranted all-floor intercom warnings from the big desk of old Steely Eyes. But none came. We stopped working. We cheered. We whooped and hollered. Most in the creative department had no idea why, but we jumped around madly at replays of Jonty’s athleticism. I joined in the jubilation and I enjoyed it.

As a sportsman I was happy to see those who thought sport a frivolous distraction buoyed by the spectacle. The tournament came to an end and the television set was returned to its place in the boardroom. But South African football, too, was about to announce itself on the world stage. Cameroon had unsettled the hierarchy of football at Italia90, beating favourites Argentina in the opening game and making it all the way to the quarter finals before losing to England.

Roger Milla and his team of Indomitable Lions, as the Cameroon national team were known, were invited to play South Africa in celebration of its inclusion in international competition. And a game was to be played at the Goodwood Showgrounds in Cape Town. I beamed and bounced around the studio, telling everyone about another exciting inclusion in world sport. As a footballer I might have cared too much. No one at the office bothered to watch the Durban game on TV, where we beat Cameroon 1-0. It bothered me a little, but not too much.

The next game was in Cape Town and I was sure that the proximity to the event would elicit excitement. It didn’t. The din of Goodwood was as dim and distant as a dominoes slam in Bonteheuwel. It became clear to me that the boardroom TV would not be commandeered for this occasion. I hyped up the significance of the game as much as I could, but my enthusiasm was reciprocated with nothing but disinterest. I decided that I would join those who valued the occasion enough to participate in it. I decided to go to the game. But it was a weekday, and thus a workday.

But this surely was a historic event, and I thought it a mere formality when telling my traffic manager of my intent to go. Karen was tough but fair. And she was a friend of Odie. She saw the excitement in my face, and I immediately saw the uncertainty in hers.

‘I will have to ask Boss,’ she frowned.

‘South Africa are playing Cameroon,’ I gasped. She went off to his office while I waited at the lifts in the foyer. Karen came back. And I will never forget her face – sad and embarrassed by the news she carried. ‘Boss says that if you go, we have no choice but to issue you a letter of warning.’

My lip trembled and my eyes welled up. Karen’s eyes welled up too. I turned to the lifts and pressed the ‘down’ button. It was a long way down from the red floor to lone black person. I had celebrated and rejoiced in the inclusion on the world stage of our national cricket team even though they were white. I expected the same jubilation and support for our soccer team, who were a better reflection of our demographics, and it hadn’t been forthcoming. I knew no chants for the football occasion, but I was at no loss for words on my way to the game. ‘Fuck you all, fuck you all, fuck you all . . .’ I sang loudly in my car.

The chant was to stick in my head and stay. I was bitter. Everything felt so wrong. And soon after voicing my anguish at the unfairness of it all to a few colleagues, I realised that my plight was seen as being ‘uppity’ or unreasonable. Maybe Boss had seen it as no more than an opportunity to finally get rid of me. And that would’ve been fair enough. Not acknowledging football, our multi-racial team and the excitement of inclusion by the majority, hurt me more. Football was only a thing when the English FA Cup was televised. Then the agency bar would be open, everyone dressed up and boisterous on the Saturday of the Wembley final. And I would be there, excited that others were too.‘Sunderland, Sunderland, Sunderland,’ I sang along and smashed pint glasses with Jembo.

The history of colonisation can be rewritten, righted and the glorious saviour it was made out to be exposed as a lie. But when your brain itself has been colonised, no amount of writing will ever change it. All you can do is sheepishly admit that you provided the coloniser free board and lodging. And it’s almost as hard to swallow as a Guinness down the Aran jersey-constricted neck on St Patrick’s Day. I enthusiastically participated in those occasions too.

We packed the work pub on a Saturday to cheer on Sunderland, yet I was alone in cheering our national team. My treatment and being singled out, although unfair, was not unexpected or scandalous. It was comfortable and deliberate. In retrospect, it was systemic.

Quotes out of: But he speaks so well

‘Communication is not a competition, it’s not a race, it’s not about a winner and a loser . . . Here’s the thing with communication: it’s about relating.’

‘You cannot control how people hear you or interpret your words, but you can give them clarity in the way you speak that leaves no room for misinterpretation.’

‘. . . any relationship in your life is going to give you the opportunity to look at your own behaviour and the space to learn new ways and evolve, if you let it.’

‘Love means something different for everyone. So, it’s important to specify to yourself and the people in your life what loving you looks like and sounds like.’

This extract has been published with permission from Tafelberg.