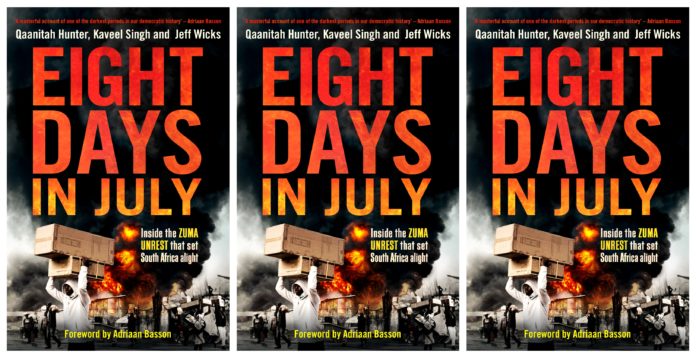

In July 2021, with the imprisonment of Jacob Zuma, dramatic and violent scenes of unrest and looting unfolded in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng. Piecing together the full story, award-winning journalists Qaanitah Hunter, Jeff Wicks and Kaveel Singh have put together a riveting first-hand account of what really happened.

An extract has been republished below with permission from the publishers.

The working theory proffered by politicians aligned to President Cyril Ramaphosa was that the unrest was carefully planned by his political opponents, whose aim was to ignite a mass uprising in an effort to delegitimise his government. By targeting places of economic activity and food supply chains, a popular revolt by the poor and hungry would be ignited, and an uprising would organically spread. ‘The plan was just to destroy everything else, there must be agitation and remove this government,’ said Deputy Minister Zizi Kodwa. He said the master plan was nothing else but to unseat Ramaphosa.

‘To an extent, they wanted to destabilise the country and they also planned what is called in a right-wing language, a lone wolf must start racial tension and racial war in South Africa,’ he said. Kodwa expanded on his claim that the instigators appeared to be former MK operatives, some of whom worked in the Security Cluster.

‘The analysis shows that the targeting of water treatment plants, cutting of fuel supplies, disrupting food and medical supplies is typical to MK training. It is our understanding that they are planning to attack the harbour and other places that will cut off food supply next.’

But how was it allowed to happen? The blame game in the Security Cluster had begun with accusatory fingers pointed between the SSA, SAPS and even the army. Politicians blamed securocrats, who in turn subtly pointed the blame at politicians. A comment by then Defence Minister Nosiviwe Mapisa-Nqakula initiated the quibbling when she told Parliament that intelligence reports of attacks on malls and shopping centres had been received too late.

‘This was an eye opener for all of us. This was a learning curve. We were nearly caught with our . . . I don’t want to say pants down, but I think that is what happened,’ Mapisa-Nqakula told MPs. She apportioned blame to a lack of intelligence, but then State Security Minister Ayanda Dlodlo vehemently rejected any assertion that there had been an intelligence failure, insisting that intel had been shared long in advance. Her deputy at the time, Kodwa, too acknowledged publicly that even before Zuma had been imprisoned, intelligence had pointed to a ‘big plot’ for domestic instability and plans for a popular revolt.

In investigating the assertion that the unrest was an intelligence failure, we mined hundreds of documents, briefings and reports from across the Security Cluster that pointed to warnings of what was to come. There had been clear warnings from the intelligence community of what lay ahead before Zuma had been detained.

But police complained that the intelligence they had received was sloppy and, at best, ‘told us what we already knew’. However, Minister Dlodlo maintained that the unrest was a resultant failure by police. This is where SSA sources pointed fingers at CI in relation to the failures in detecting organised crime that had been carried out during the looting, which included the pillaging of malls and targeting of ATMs. In the eight days of chaos, R120 million was stolen from 1 227 ATMs. As many as 256 of these cash cows had either been ripped from their concrete mountings or blown open using explosives and hand grenades.

Staggeringly, 36 were stolen and remain missing. The leadership crisis at CI was further blamed for the intelligence failures, leaving cops on the ground directionless and giving looters free rein for days without intervention. National Police Commissioner Khehla Sitole later told Parliament that the instigators knew specificities of police deployment and knew police members were scattered to enforce lockdown regulations. ‘At the beginning when everything started, all our force levels were in the various areas of deployment, in terms of COVID-19.

Because of the enforcement that is a requirement. That also includes roadblocks and other operational activities . . . So, whoever then started modus operandi [sic] was aware that the force levels are actually scattered. And they realised very well that at the time the activities started, then they were going to beat us with a reaction time. Secondly, they also capitalised on environmental design factors.’

While the police’s failures in stemming the unrest were on full display during the zenith of the unrest, they were ameliorated by a show of force later in the week. At an ultimate cost of R350 million, police deployed 4 500 uniformed police officers – almost half of the total number of personnel deployed daily throughout South Africa – to ensure stability in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng. They also called up 2 245 SAPS reservists to swell their ranks.

By the time the chaos died down, SAPS had conducted 112 roadblocks with 9 642 vehicles stopped and searched. A total of 2 097 vehicle checkpoints had been staged. Roadblocks were a major part of NatJOINTS recommendations to hinder mass mobilisation.

Further, police conducted 190 patrols on national roads, with 18 530 people searched in the week of unrest and over 760 premises searched. Police also recorded 336 incidents attended by the Public Order Policing Unit. As the active looting and violence waned, police made over 2 200 arrests in both provinces, with the focus shifting to instigators of the unrest.36

NatJOINTS noted that, by Thursday, protests remained coordinated, instigated and sporadic, ‘making [them] difficult to contain’. ‘Criminal and opportunistic elements capitalized on the situation provided,’ they noted. The protests were characterised as the use of disgruntled communities, especially in informal settlements.

It noted that the protests began with the targeting of roads and tolls ‘and has since evolved into looting and targeting of trucks and malls’. Other modi operandi included the use of petrol bombs, discharging firearms, torching trucks, targeting law enforcement, and threatening economic key points and places of interest such as the ports of Durban and Richards Bay, King Shaka International Airport and the SABC offices. A common thread included the use of tipper trucks to block roads with rubble, removing vehicle registrations of cars used and relying on youths to fuel the protest.

The deployment of soldiers provided respite for police who, admittedly, were completely overrun. By Thursday a total of 10 000 soldiers had been deployed in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng. At first, the military plan was to have 2 500 soldiers on the ground, broken up into one subunit of the army in each province on standby, with the exception of the flashpoint provinces of Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal, which were each to have three subunits on the ground. Unrelenting violence and looting forced the president to increase the deployment to 10 000, with plans to further bolster the number to 25 000.

The projected cost of one month of army on the ground was in excess of R615 million. The main tasks of the soldiers were to protect national key points, harbours and airports, fuel refineries, Eskom’s power generating plants, the Union Buildings and Parliament. They were also tasked with guarding and protecting the road freight industry, conducting foot and vehicle patrols, assisting with vehicle control points and roadblocks, and enforcing Disaster Management Act regulations.

The presence of soldiers in suburban areas is an anomaly for democratic South Africa, but the rolling in of armoured personnel carriers after days of lawlessness was widely celebrated by ordinary citizens as an effort to reinstate law and order. By Thursday, incidents of violence began to taper and, with police no longer engaged in running battles with mobs, the focus turned to the arrest of instigators, processing those nabbed for looting and public violence, and quantifying the impact of the devastation. Incident reports from Thursday showed that drunk protesters had tried to block train tracks in Malvern in Durban by lying on the rails, but had quickly run off when police had arrived on the scene. Looters had returned to the Clover warehouse in Pinetown, which had been looted earlier in the week, with mobs circling back to see what was left.

In Groutville, an hour from Durban along the N2, a group of youngsters broke into the Nonhlevu Secondary School and made off with stolen goods before they were arrested and the stolen items recovered. This was one of more than 158 schools that were hit by violence in KwaZulu-Natal. Some schools were looted, others torched and damaged to the tune of R138 million. The immediate consequence of the unrest was the economic impact felt through snaking queues for basic food and fuel.

A report from NatJOINTS on 15 July noted that the looting and destruction of the main food distribution hubs in KwaZulu-Natal and other distribution centres held ‘the potential for food insecurity in the province with the added risk of protests in demand for social relief ’. Shops that had been spared from looting and torching saw queues kilometres long, with shortages of basic necessities such as bread and milk. The shortages were exacerbated by panic buying out of fear that there would be countrywide food shortages. The Security Cluster warned that there was a potential for conflict between residents perceived to be from affected areas, who travelled to unaffected areas to buy food and other necessities, and residents who lived in these unaffected areas.