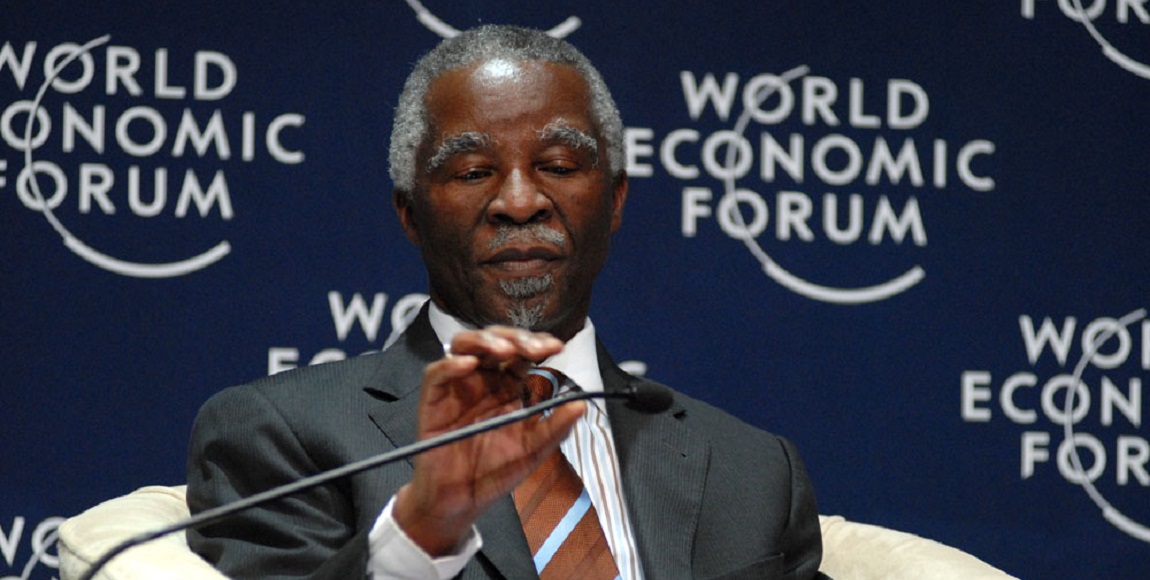

A number of Zimbabweans do not want South Africa or the Southern African Development Community (SADC) to intervene in the ongoing crisis. A citizen in Bulawayo started a petition to stop SADC from interfering with the political transition in Zimbabwe on Thursday. The petition has been signed by over 19 000 supporters. It aims to reach 25 000. Former South African president Thabo Mbeki has been heavily criticised for his silence during the violent 2002 and 2008 Zimbabwe elections. Mbeki also mediated before the 2008 election and later in the year became the chairperson of SADC. The Daily Vox explains how Mbeki sustained Mugabe’s hold on political power.

When the SADC heard that the people of Zimbabwe are suffering under Mugabe’s rule, they took no action, but when they have heard that Mugabe is under house arrest, they have quicky sent envoys. The SADC loves Mugabe more than the people of Zimbabwe’

— Nathan Themba Dube (@kalikochi) November 16, 2017

Firstly, what is Thabo Mbeki’s “quiet diplomacy†policy?

Mbeki described his much criticised “quiet diplomacy†approach as based on “unwavering determination to respect the right of the people of Zimbabwe to determine their own future.â€

What happened in the 2002 elections in Zimbabwe?

The Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (Zanu–PF) has ruled Zimbabwe since independence in 1980. Zanu-PF’s power was contested in elections in 2002 and 2008 – with violent consequence. And South Africa – under former President Thabo Mbeki at the time – took a soft stance on it.

In the hotly contested 2002 elections, Robert Mugabe won 56.2% of the vote and opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai of the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC-T) won 42%. Mbeki sent two observer missions to monitor the 2002 elections. The two agreed that that the election results reflected the will of the Zimbabwean people.

Dear SADC , AU, EU, US

We plead with you to stay out of the political stand off in Zimbabwe.

37yrs of your errors of commission and omission has hurt us. We are very clear what we want and you can’t help.

Sincerely

Trevor Ncube

Long Suffering Citizen who loves Zimbabwe dearly— Trevor Ncube (@TrevorNcube) November 17, 2017

However, Mbeki ignored the findings from the South Africa’s Judicial Observer Mission sent to Zimbabwe in 2002, now known as the Khampepe Report.

What’s up with the Khampepe Report?

Then-high court judges Dikgang Moseneke and Sisi Khampepe were part of the mission and compiled the report. In it, the two judges acknowledged that opposition parties participated in the elections and agreed there were no counting irregularities. However they said circumstances surrounding the elections meant the elections “cannot be considered free and fair.â€

The report said the 2002 elections were marred by the killing of over 100 people in the pre-election period, most thought to be supporters of Tsvangirai; violence and intimidation by by the youth arm of Zanu-PF; violence and threats of violence, arson and hostage taking relating to the elections that “curtailed freedom of movement, freedom of speech, freedom of assembly and of association of votersâ€; an undetermined number of people prevented from voting by the reduction in urban constituencies; bias and partial treatment by police, state media and others; and drastic amendments to electoral laws by Mugabe that confused and made voters’ roll opaque and subject to manipulation by officials.

The Khampepe report was only made public in November 2014 after a six-year legal battle between the Mail & Guardian and South African government. Thabo Mbeki, Kgalema Motlanthe, then Jacob Zuma fought against its release to the public. Despite the fact he ignored the contents of the report, Mbeki faced no consequences and maintained that the 2002 elections were free and fair.

The Thabo Mbeki Foundation declined to comment.

What happened in the 2008 elections?

The 2002 elections set the scene for 2008. During the March 29 elections, MDC-T won 99 house of assembly seats; Zanu-PF 97 and Arthur Mutambara’s MDC-M faction won 10. Zanu-PF, aided by the military and Zimbabwe Electoral Commission officials, delayed the announcement by over a month amid speculations of rigging.

When the poll results were released on May 2, Tsvangirai had beaten Mugabe by 48% to 43%. But Tsvangirai needed 50% plus one to win, which led to the electoral commission declaring a runoff.

The runoff was supposed to take place 21 days after the first round, according to Zimbabwe’s Electoral Act, but was held later on June 27. Countrywide violence erupted in the run-up to the election, coordinated by war veterans, the Zanu-PF military and security force members whose troops were deployed countrywide. Food aid became another election tool because of food shortages. Zanu-PF controlled its distribution and public MDC activists and supporters were denied supplies according to the Mail & Guardian report.

Tsvangirai withdrew on June 23. He said 86 people were killed and 10 000 injured in the violence, about 10 000 homes destroyed, and 200 000 displaced. Two days after the election, Mugabe was declared the winner with 90% of the vote.

When Zimbabwe has faced real security issues, including 2016 uprisings and 2008 election violence, SADC was nowhere to be seen. South Africa said there was “no crisis.”

Zim is at its most peaceful today. SADC wants to come and ruin it.

Please just stay out of it.

Bob must go.

— Fadzayi Mahere (@advocatemahere) 16 November 2017

What did South Africa do to uphold democracy?

Mbeki – who was the chairperson of SADC in 2008 – was the chief mediator between Zanu-PF party and MDC-T in the build-up to the election.

Mbeki chose to allow the events in Zimbabwe to take their course then declared them legitimate. He endorsed the 2002 elections despite concerns expressed by observers from Commonwealth nations, Ghana, Japan, Norway and SADC. Mbeki ignored the findings of the Khampepe report.

In 2008, Tsvangirai wrote an open letter and said Mbeki was not fit to serve as the region’s mediator in Zimbabwe’s political crisis due to his “lack of neutrality.” He also accused Mbeki of facilitating a controversial weapons delivery from China to the Zimbabwean military. Following the 2008 election, Zimbabwe’s economy took a plunge and thousands of citizens fled to other countries to escape the political and economic crisis.

When the Khampepe report was released in 2014, Tsvangirai told the Mail & Guardian had Mbeki disclosed the contents of that report at the time, SADC could have pushed for free conditions in the 2008 elections, which would have opened up democratic space in Zimbabwe. Instead Mbeki had chosen stability over democracy, he said. He chose to honour “quiet diplomacyâ€.

Mbeki was silent during the controversial elections despite that he is a forerunner of the African Renaissance which is about: social cohesion, democracy, economic rebuilding and growth and the establishment of Africa as a significant player in geo-political affairs.

Zuma should please just stay silent! SADC and AU watched and stayed silent as Mugabe carried out atrocities against his people. Let fate for Mugabe take its course #Zimbabwe

— #MyNewZimbabwe (@ChelleChipato) November 15, 2017

What should South Africa have done in 2002 and 2008?

Democratic Alliance shadow minister of international relations and co-operation Stevens Mokgalapa told The Daily Vox that the costs of the Zimbabwean crisis started in 2002 and continued in 2008 when the elections were rigged. He condemned Mbeki’s silent diplomacy and said Mbeki’s silence meant he chose “stability over the will of the people and democracy.†The whole crisis was happening under South Africa’s nose under the leadership of Mbeki with his quiet diplomacy, he said.

Mokgalapa said South Africa should have taken decisive action the way Senegal did during the elections in The Gambia earlier this year. Senegalese leader Macky Sall led an Economic Community of West African State intervention in The Gambia against the leader Yahya Jammeh, who had forcefully been in power since 1994 and refused to allow democratically-elected Adama Barrow to assume power. “Mbeki ought to have taken the leadership role and ensured the will of the people was respected,†Mokgalapa said. “[Senegal] paved the way for a democratic dispensation and that is what needed to happenâ€.

Can today’s SADC meeting bring about a successful resolution to the #Zimbabwe crisis? @maggsonmedia will have the results at 3pm on #DStv403

— eNCA (@eNCA) November 16, 2017

Additional reporting by Ethel Nshakira