The City of Johannesburg is on the brink of impending doom. Well, that is according to a Sunday Times report from November 25. Quoting experts in the mining industry, The Sunday Times reported that gas and fuel lines in the city’s underground could be at danger of damage due to illegal mining activities.

Speaking to The Sunday Times, Conel Mackay, the Johannesburg infrastructure protection unit head said: “The city faces a disaster beyond imagination.”

The Johannesburg executive mayor Herman Mashaba said he has tried to get help from the department of mineral resources (DMR) to no avail.

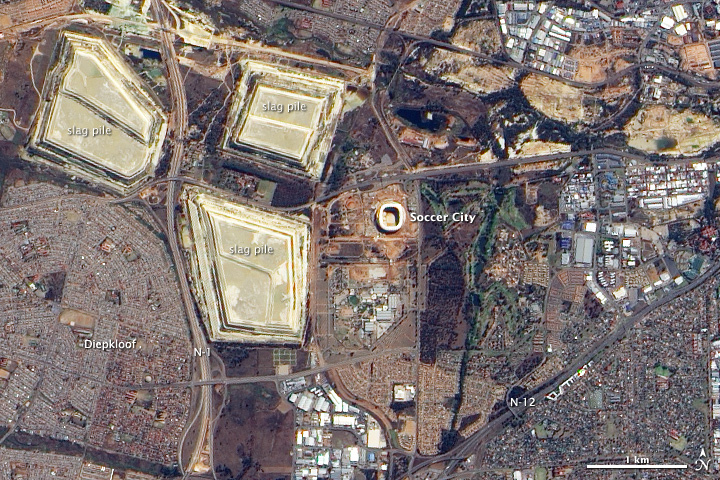

The report goes on to say that Transnet and Sasol have raised concerns about the potential disaster but the government hasn’t taken any action. The key parts of the city that are reportedly at risk includes the M1 double-decker highway and the M2, sections of Soweto and the 94,000-seat FNB Stadium.

Mashaha raised the concerns around the issue in 2017, saying that illegal mining threatens the Nasrec area. At the time, Mashaba raised concerns about the intersection of pipelines with the Sasol gas lines saying that if the illegal mining continues, the entire Nasrec precinct could go down in ruins because of the unstable land due to a possible underground explosion.

Maintaining that there isn’t any immediate safety problems for people living in the area, the DMR have ordered an investigation by the Council of Geosciences (CGS) to assess whether the pipeline has suffered from long-term damage. In a statement released on November 26, the department says they have initiated a ground stability study to be undertaken in the Johannesburg area with immediate effect. The CGS have been tasked with assessing whether there is any long-term damage to critical infrastructure installation with results from the study expected in the next two weeks.

David van Wyk, lead researcher at the Benchmarks Foundation, said in a statement that the reports claiming that small scale mining by so-called zama zamas poses a threat to Johannesburg’s safety are completely baseless.

Van Wyk said: “These allegations are part of a campaign at local level to fan the flames of xenophobia in an attempt to secure the votes of coloured populations in Riverlea, Davidsonville and Fleurhof.” It is a further part of the department of mineral resource’s attempt to divert attention from the court victory against it on Friday last week which gave communities the right to say no to mining,” van Wyk said.

Van Wyk is referring to the victory by the Amadiba Crisis Committee on behalf of the Xolobeni community to say no to mining on their land. After years of court battles with the DMR, the North Gauteng High Court ruled in favour of the community saying that mining companies and the government have to gain full and informed consent from communities before granting mining licenses on communal land.

The department has vowed to work through the National Coordination Strategic Management Team (NCSMT), on how the matters of illegal mining can be addressed. Through the task team, the department works to eradicate illegal mining through the promotion of legitimate mining, rehabilitation of derelict mines and sealing of holes, and policing and law enforcement.

Van Wyk said the DMR has given licenses to mining companies to operate on land situated on top of gas pipelines, and issue which has not been addressed.

In South Africa, artisanal or small scale miners operate outside of the law and are regarded as illegal. They do not hold any mining permits, carry out their work on private land, and can be prosecuted for their land. Zama zama usually refers to mining activity which is directly linked to criminal activity. There has been a push to increase the amount of mining permits granted to small scale miners, however the process can be long and expensive for the miners.

In June 2018, the DMR granted two mining permits to thousands of artisanal miners, giving them legal access to 500 hectares of land in Kimberley, Northern Cape. This was all part of a move to regulate and formalise the industry and the activities of the artisanal miners. More than that however, the Minerals Council of South Africa were told that they should be pursuing a more comprehensive policy that will tackle the causes of illegal mining.

Previously, The Daily Vox interviewed Kgothatso Nhlengethwa, a mining geology researcher specialising in artisanal mining, who said: “The problem is with access, of actually being able to start the process, actually getting mineral rights from the DMR office. Also what most people don’t know is that to get a mining permit, you need an environmental management plan. These have huge costs especially for a small-scale miner.”

Another huge problem with illegal and artisanal mining in South Africa is that there just isn’t an concrete information on the number of zama-zamas who are engaged in mining, how much they produce, and how much revenue they create for themselves, and where exactly the products of the mining end up in the sale process. It is estimated that there is around 30,000 artisanal and small scale miners (ASM) in South Africa – who rely on the mining as there only source of income especially with the high levels of inequality that can be found in South Africa.

Unless the government creates solutions which deal with the source of poverty and inequality – artisanal and small-scale mining is going to continue despite the dangers it poses to the miners and their surroundings.