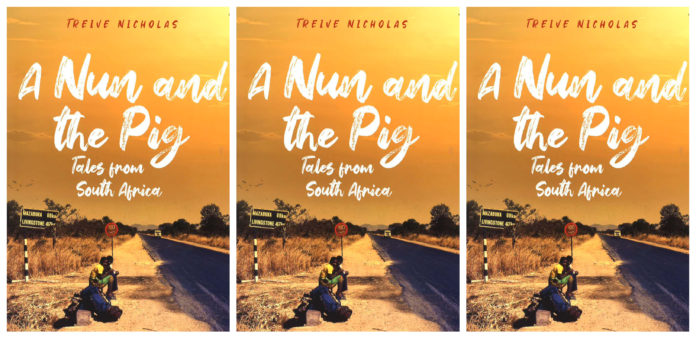

Looking back on this year forty years later, A Nun and the Pig: Tales from South Africa offers a remarkable insight into South Africa during apartheid. The book features Treive Nicholas’s lived experience ranging from the surreal to the heart-warming; the wonderful to the tragic. an extract has been published below with permission from Jonathan Ball Publishers.

Part of the Zimbabwe independence celebrations in 1980 included a large art exhibition in central Harare that I happened upon quite by accident. As well as displaying regional black art, which was stunning, it also celebrated the black liberation movement and the partnership between the freedom fighters of Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) and Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (FRELIMO), the communist-backed government of Mozambique. Numerous bright posters and leaflets around the exhibition space conspicuously promoted black power, the armed struggle and the role of Marxist–Leninist philosophy to build a better future for the workers. For me, coming from a conservative suburban British background, this was all very unfamiliar and a touch unnerving. I was in a hall that was unambiguously celebrating communism and revolution, and I was just a tad out of my comfort zone. These were not the usual topics of celebration back home in the leafy streets of Guildford, where local political parties usually wrestled with the challenges of new one-way traffic systems and bus timetables. I’d read about the French and Russian revolutions, and I knew that both had got a little out of hand with the Sans-culottes and Stalin’s ‘Great Purge’ causing more than their fair share of misery. The messages and themes of black liberation were bold and undiluted. While the sacrifices of those lost in the armed struggle were reflected upon, the main focus of the posters and leaflets was on a prosperous future for black people, led by ZANU-PF and FRELIMO. Who was I to challenge the wisdom or otherwise of revolutions? I didn’t even know what Marxism really meant.

Sensing that I was witnessing a piece of African political history, I politely requested and received a handful of the communist-themed leaflets and bright posters, stuffing them into my rucksack and forgetting about them. After a few days I headed back to South Africa, and Umtata in Transkei.

It would be fair to say that my transit through the Botswana–South Africa border post did not go well, starting with my arrival. As we pulled up, I could see the border guards eyeing me.

Mistake #1: I was in the back of a pickup driven by black men, not the other way around as was customary in these parts. Furthermore, this mistake was already drawing attention to me, when I really wanted to be inconspicuous.

Mistake #2: I went to the wrong passport counter. Without a word, the border officer who stood on the other side of the counter slowly moved his head from side to side to indicate something was wrong. He deliberately did not say what was wrong and was terribly agitated, refusing to take my passport from me. Then I realised that I was at the counter for black people, so I stepped one metre to the left to the counter marked ‘Whites’.

Mistake #3: I was British. The pugnacious border officer was now very clearly my adversary. He was short and stout, with a crisply ironed uniform, and was obviously uncomfortable speaking English, so he did not. He must have been a local Afrikaans lad, with a few historical grudges weighing heavily on his chipped shoulders. For the most part he stared at me, not saying a word. Not one. A colleague in the office watched us. This must have been good sport for him. But it was all extremely awkward and tense for me.

Mistake #4: My passport was replete with stickers showing multiple entries in and out of Transkei, as well as border stamps from Swaziland, Zimbabwe and Zambia. He smelt a rat and wouldn’t return my passport. In fact, he wouldn’t stamp it for re-entry into South Africa. I tried to stay calm, conscious not to goad him.

Mistake #5: He could see my rucksack in the back of the pickup van. His eyes honed in on it, his suspicions raised. Now my concerns shot up, too. Although I didn’t know a word of Afrikaans, I understood the instruction he bellowed at a tall young soldier standing guard at the border post. Still keeping a firm grip on my passport, he instructed the soldier to search my rucksack. Shit. This was getting serious. This wasn’t supposed to happen. I never really thought Plan B would come into effect. More to the point, I wondered if it would work as I tried to keep my anxieties hidden from the arrogant little fascist who switched his glare from me to the soldier and back again, not uttering a word.

The soldier, in beige field fatigues, got to work pulling open the straps of the rucksack. My pulse nudged up a few notches. Stay calm, I told myself. For God’s sake, don’t look stressed and give the game away. Would he find the rucksack lining and the black liberation material I’d hidden? The rucksack was now fully open. Shit! In went his arm and out came three soapstone figures from Swaziland, sweaty T-shirts, a dusty fleece, underwear that had endured two stomach upsets, a pair of boots, biltong, toothpaste, crusty socks and quite a bit of dust. The ripe odour must have served as a repellent, as the soldier stopped, shook his head and roughly stuffed everything back inside. He’d seen enough to convince himself that it was just travel stuff.

Could I relax? No.

The passport officer still wasn’t satisfied. He disliked me a lot and was convinced I was hiding something, so he went from staring at me in silence to bluntly asking me, in his very thick accent, why I had travelled to South Africa from Transkei so many times. He insisted this was not normal. He seemed fond of normal. The five-foot-nothing gatekeeper was bristling, his agitation visible. My passport lay open on his side of the counter, his piggy fingers leafing the pages. And why had I gone to Swaziland, Zimbabwe and Zambia recently? Who would want to go to these dreadful places? Everything I’d done represented irregularity and deviance. Without inflaming the situation, I explained my job at Ikhwezi Lokusa School and a desire to see southern Africa, emphasising the natural beauty and landscape. He was most certainly not happy with my explanation. For him, there remained the distinctive whiff of a rat in the air. He knew I was talking bullshit and he really didn’t want to give me an entry stamp, but he couldn’t nail me, and reluctantly caved.

Thump! He stamped my passport and slid it across the counter. Plan B had worked. By the skin of my teeth I’d got away with my subterfuge. His glare, his stiff, upright posture and his tight lips did not mellow, even as I hopped into the back of the pickup van with my rucksack at my side. Through the dust I could see him still watching intently as we drove off. For him, the smell of rat still lingered.

That had been way too close for my liking. And so, I hitchhiked back to the sanctuary of Ikhwezi Lokusa Special School in Umtata, with my communist contraband still intact. Finally, my 6,500km hitchhike around South Africa, Swaziland, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Botswana, and Lesotho had come to an end. I was still in one piece, just, and in desperate need of a warm shower.

The book is available at all good bookstores and online.