Many of the movements during so called #FeesMustFall era did not see demands such as curriculum reforms, living wages or even free education as something being strictly limited to higher education. However, movement fracturing, state repression, the closing down of popular education spaces, and a growing cynicism among students from below have made it increasingly difficult for broad-based coalitions to grow beyond the margins.

I think we begin to undermine our own abilities to work with one another when endless fights for the moral high ground through grandstanding transcend its use as a merely a tactic of disruption, and become the modus operandi for ensuring and acquiring control over one another.

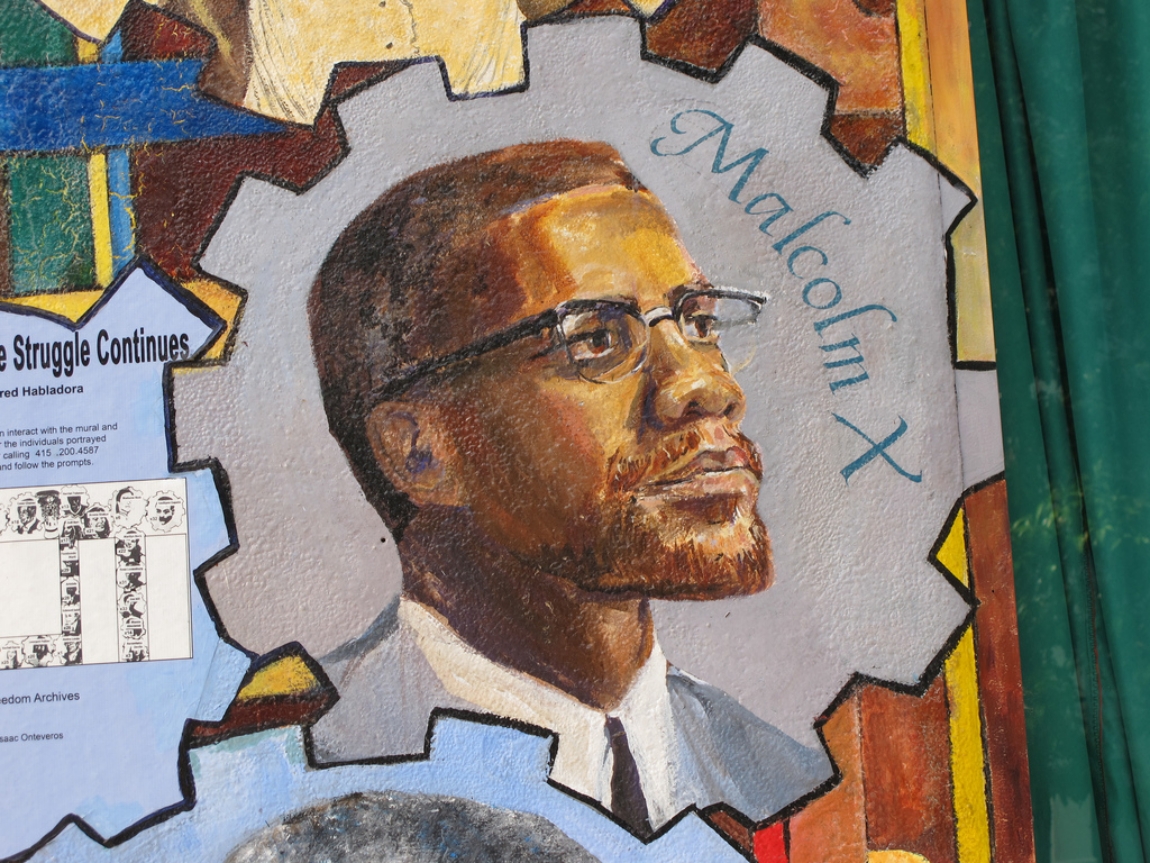

The story of el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz, earlier known as Malcolm X and born Malcolm Little, in all its contradictions, offers us many useful sites of reflection to think through this tendency.

Malcolm Little was born into poverty under US segregation in 1925 and was said to have lost his father to terrorist actions taken by the Ku Klux Klan – although it was officially declared a suicide. After their life insurance company refused to pay out, Malcolm’s remaining family was torn apart by a social worker system mediated by the state that – instead of offering support – criminalised his mother’s mental illness and irrevocably split the family. After moving to Boston with his aunt Ella Little-Collins, he drifted out of public schooling and found himself involved with numerous criminal activities in Harlem, New York where he was later arrested. While in prison he was able to further his education through the encouragement of some of his siblings who had joined a group called the Nation of Islam (NOI).

The NOI was then headed by Elijah Muhammad, once known as Elijah Robert Poole. The NOI was known as a religious, black nationalist movement whose primary pillars stood against integration but insisted on black self-determination, reparations through land reforms, and strongly opposed military drafts to the US Army – notably with the Vietnam war.

Among their social programmes at the time, Malcolm had been working with black prisoners and assisting them get back on their feet through the movement, often employing and housing – as in the case of Malcolm – converts. Malcolm X, who felt a deep indebtedness to Muhammad – who was described as a prophet by the movement – became his disciple and among his most talented speakers.

At the time as part of the NOI doctrine, it was believed that an ancient black scientist Yakub, 6 600 years ago, invented the “white race” on a greek island called Patmos. This teaching emanating from the writings of co-founder Wallace Fard Muhammad, deviated from orthodox readings of Islam which Malcolm X would go on to encounter later in his trip to the Middle East.

Malcolm X famously went on to fall out of favour with Muhammad after he spoke critically and “out of turn” on the passing of John F Kennedy, famously declaring that “the chickens have come home to roost,” and linking the affair with the US sanctioned murder of Congolese independence leader, Patrice Lumumba. Suppressed extramarital affairs and other “moral” contradictory practices of Muhammad discovered by Malcolm deepened the growing rift.

During his later tours internationally and in Africa in particular, his views began to transform to connect struggles across contexts critically – particularly questions of racial hypocrisy from both the left, right, and the American to Soviet – in increasingly political speeches that brought to the centre the imagination of what pan-Africanism and Third Worldism could look like. Through fiery speeches, he connected the Bandung conference to the plight of African Americans in the ghettos, a feat rarely achieved by many prominent civil rights leaders of the day.

Among the many lessons we can learn from in this borrowed memory is the importance of highlighting the circumstances around his death. While controversy around the dynamics remains inconclusive, many still believe the CIA capitalised on the rivalries and conflicts within the NOI to cut Malcolm’s expanding influence and increasingly international influence.

In our own small contexts today, it is worth reflecting on how groups and people who control their followers with emotional blackmail or other forms of coercion rely on limiting one’s social world and controlling the images and boundaries of its simplistic cosmology. We can learn from Malcolm that to broaden our horizon – be it for the plight of the Palestinians, the Somali, or the Congolese – we do not diminish the urgency and importance of our own, but unlock possibilities for tomorrow that can never exist if we are to rely on our own out of sentimentality or chauvinism.

In this brutal age of neoliberalism we owe it to ourselves to revive discussion on primacy of social programmes of the movements we herald, instead of simply leaning on their most popular quotes and speeches to score points against people and groups we do not like.

The battle against depression and defeatism in activist spaces is an urgent and ongoing one but in youth spaces in particular I think it is becoming on to us to challenge all forms of cynicism that undermine the prospects of for a better tomorrow. Because if we allow this to set in and calcify the horrors of the present predatory elite, it will be nothing compared to the corruption of tomorrow done in the name of “well, we’re all complicit anyway”.

If we continue to close down the possibilities for each other to change to the extent that only the most cynical and ruthless among us are able to survive then, my friends, the political world of tomorrow is going to be a scary one: we are well set to be our largest and most dangerous enemies.