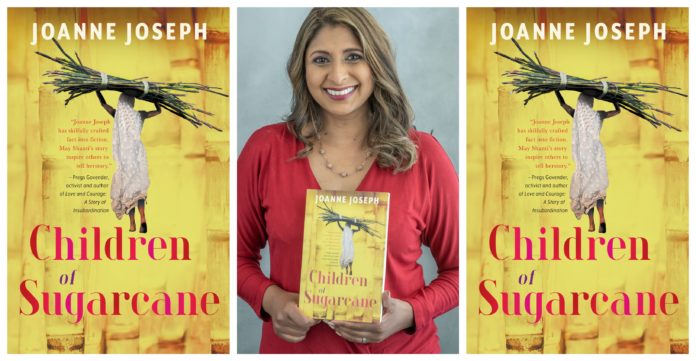

In Children of Sugarcane, writer and media personality Joanne Joseph, weaves a deeply political and personal tale of indenture. Joseph introduces readers to Shanti, a young woman from Madras who goes to Natal to work as an indentured labourer.

Background

The history of indenture in South Africa is part of a violent and traumatic history. However, many parts of South African history including colonialism and apartheid is overlooked and not reckoned with properly. The same can be said of indenture. Joseph’s book is an attempt to ensure those difficult conversations are had.

READ MORE:

“The Lie of 1652” debunks colonial and apartheid land myths

Here is a quick history lesson for those unsure about what indenture is. From around 1860 to 1911, hundreds of thousands of Indian people were brought over from India to work on the sugar plantations in the Natal Colony. However, it was not as simple as that and while fictionalised, Children of Sugarcane shows a little glimpse in the difficulties and hardships the indentured labourers had to endure. Their labour was sold to the British colonialists and they were made to endure all kinds of difficulties.

In the book, Shanti makes an impassioned plea that summarises what indenture actually was. “Let word get back to India that this masterful transaction with Queen Victoria they are so proud of is a ruse to abuse us and profit off our pain,” Shanti says in the book.

Writing the book

Speaking to The Daily Vox, Joseph said when she started the book, she had no idea how to approach the writing of historical fiction, even though she had read many novels in that genre. “So there were many moments over the years in which I was severely strained, flummoxed even, during the earlier drafts, grappling with everything from structure and form to balancing historical content with fiction,” she said.

Read more:

Bunny Chows And Guptas: The Heritage Of South African Indians

The book follows Shanti as she leaves India to avoid an arranged marriage. She is told stories of South Africa and the Natal Colony as a place where she can find a better life. However, once she arrives, the reality is far from that. She and the others are made to work long hours and live in terrible conditions. The women received less money than the men and were often victims of abuse from both their fellow male labourers and their masters.

The book is also told in the form of a diary. It begins with Shanti back in Madras – many years later. Her daughter Raksha finds her mother’s writings and then begins to learn a little more of the secrets her mother has kept from her. Along with the mother and daughter, there is another woman character who plays a central role in the book. This is Devi, Shanti’s closest friend and confidante on the plantation. Joseph said both Devi and Shanti were modelled on individuals she is close to. However, this didn’t make them easier to write.

The characters

“It was complicated situating these two characters in the nineteenth century where the circumstances were quite different. I had to ask myself: thrown into that milieu, how would they react? Would they rebel or comply,” she said. Joseph said Shanti’s daughter, Raksha, was probably the most difficult character to write. It is through these three women that readers are shown the true cost of indentured servitude.

Most importantly, they show why it is important that people learn and never forget this history. In South Africa, historians and academics like Goolam Vahed and Ashwin Desai have done extensive work on indenture. However, this work is concentrated in the academic space.

Joseph said: “Many South Africans of Indian descent do not even know about the suffering and hardships which characterised their ancestors’ indenture. We often speak of decolonisation these days, but how do we decolonise our world view and institutions without understanding what constituted colonisation?” She hopes the book offers a small worldview into this history.

READ MORE:

Six things that Durban Indians grew up with

In that aspect, Joseph has definitely succeeded. The book is a huge eye-opener. It will leave you as the reader shocked, angered and saddened by the events. However, it will also leave the reader with a sense of the incredible strength of Shanti but also the thousands of real-life women who were indentured.

The book goes into albeit briefly how the colonialists used “divide and conquer” to separate people. When Shanti and the other labourers arrive in Natal, they are told not to interact with the “natives”. Joseph said her book “navigates certain issues which continue to plague our society”. She hopes it will “encourage readers to contemplate why we still find ourselves in this situation where racial, class and gender discrimination, among many other problems, continue to stymie our evolution as a society”.

READ MORE:

South African Indian Muslims need to look in the mirror

Sometimes academic work and even journalistic work can be isolating and not accessible to the broader public. Fictionalised work is an excellent way for people to find out more about histories and people they might ever interact with. Children of Sugarcane does that excellently.

Children of Sugarcane is published by Jonathan Ball Publishers and is available online and at all good bookstores.