COMMENT

Twenty-first birthdays in South Africa, while legally non-significant, often still carry much pomp and ceremony surrounding the idea of fully-fledged adulthood. Symbolic keys “to life” are often gifted, while some lucky others may receive literal keys – to new apartments and/or cars. The ‘key’ I received on my 21st birthday was the damning knowledge that I was being sent into an adulthood riddled with the same age-old challenges that so many black women before me had endured. By LAUREN HESS.

My mother, ever the academic, had prepared a multi-part document entitled To Lauren – a speech to commemorate the occasion. In it, she detailed the enormous responsibilities that lay ahead for me as a young, middle-class, black woman who was privileged enough to have attained a degree. More than blood, shared mannerisms or any amount of DNA; what connected me most to my mother in that moment was the shared experience of daily dehumanisation that derives from being a black woman in South Africa. The warning to steel myself against a world that would subtly continue to chip away at my dignity – a world that would more easily assume me to be a sex objects than a professor; that would continually attempt to wrestle my bodily and intellectual autonomy from me, has stuck with me to this day. Four years and two degrees later, ‘blackness’ and ‘womanhood’ – with all the nuances that intersectionality has to offer – remain markers of vulnerability in South Africa.

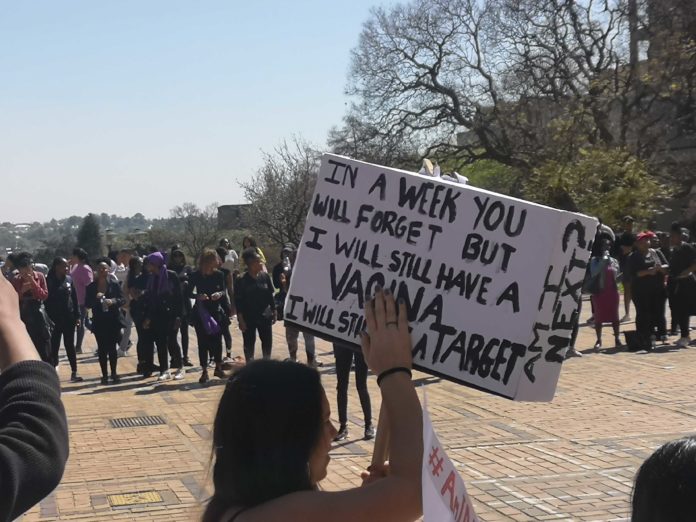

Witnessing seas of black-clad mourners on social media platforms from across the Atlantic has left me with mixed emotions. At some level, I feel distanced, removed from the incredibly brave women and allies who took to the streets to protest the brutality of Uyinene Mrwetyana’s death throughout the past week. At the same time – the trauma of those who came before me and those who will (unfortunately) still come after me have created inextricable links to the shared experience of rage, violence, and trauma that are currently unfolding on my Twitterfeed.

As women in South Africa (and around the world!) continue to beseech those in power to provide answers as to when enough will truly be enough – and why the protest and rage of 2013 in the wake of Anene Booysen’s equally brutal murder and rape could not prevent the conditions that would spur similar events six years later – I am painfully reminded of Audre Lorde’s sombre observation that “Revolution is not a one-time event.”

We cannot wait for August to roll around each year to make commitments to the safety and empowerment of women. We cannot wait for the annual release of the Employment Equity report before we point out the perennial absence of women (and particularly black women) in positions of power in the workplace. We cannot wait for women to take to the streets to begin to remark that, “Sjoe, things have gotten bad lately, hey.” Statistics have shown for years that the level of violence and marginalisation experienced by women in South Africa is nothing short of a wartime equivalent.

Mam ’Mrwetyana’s remarks that she should have warned Uyinene not to go to the post office are still ringing in my ears. The truth is that the burden of vigilance and fear that we place on women, that we call “being responsible” or “common sense” – is anything but normal. Despite the latest advances in self-defense equipment or ‘buddy systems’, without a whole-of-society approach to women’s right to safety and gender equality, the sad fact is these instructions only reinforce the idea that by dress or by behaviour, violence can be avoided. Or that, instead of addressing rapists, women should behave in a way that ensures that their safety is dependent on someone else being a target.

Gender-focused organisations, commissions, and scholars across the country continue to provide tangible suggestions to promote gender-mainstreaming initiatives and mitigate patriarchal socialisation. It is time we listen. Without sustained support from institutions and the people who fill them (predominantly men as the Commission on Employment Equity tells us), South Africa will continue to fail its women. While the protests of this past week demonstrate that it is far too late for my eighteen-year-old sister’s generation – and likely the one after hers, too – please let this revolution not be a one-time event.

Lauren Hess is a South African Fulbrighter currently based in Washington DC. A recent MSFS graduate of the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University, her writing interests include postcolonial international relations theory and the gender dimensions of development.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policies of The Daily Vox.

Featured image by Shaazia Ebrahim