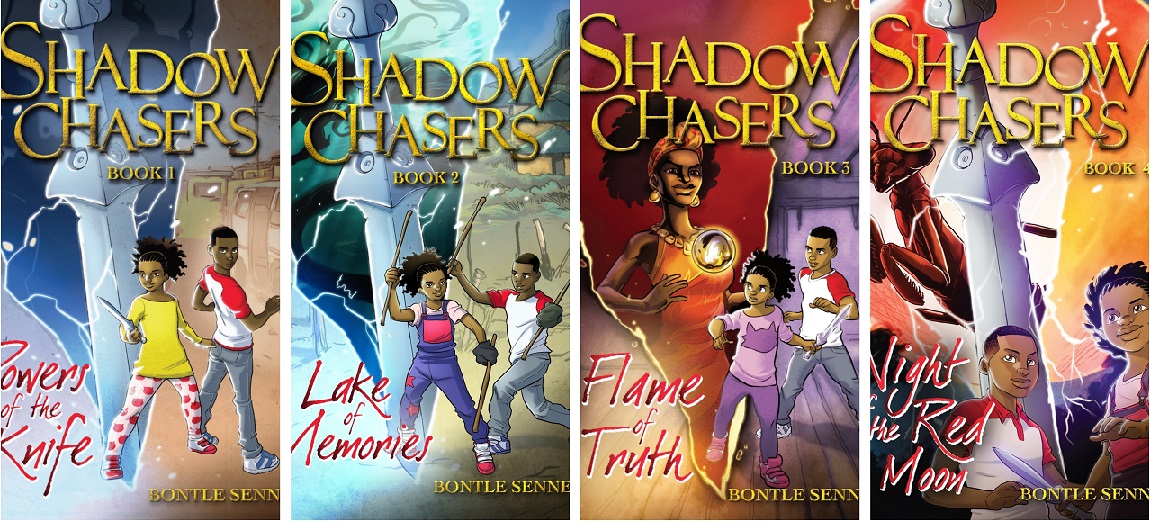

Bontle Senne writes about myth and magic and kickass girls in her Shadow Chasers series. The series is the perfect reading for 9-12 year olds and pretty much everyone else who is into contemporary, Afrocentric stories. Senne is well-known in the book world as a writer, book blogger, part owner of publishing house Modjaji Book, and general literacy advocate. SHAAZIA EBRAHIM caught up with Senne about stories, reading and writing, and feminist characters.

Can you tell me a little about your own journey with reading? What are some of your earliest memories of reading stories and what kinds of books did you read?

Can you tell me a little about your own journey with reading? What are some of your earliest memories of reading stories and what kinds of books did you read?

My earliest memories are of writing. I don’t really remember the books I read before I started writing. When I was eight or nine or 10, I actually loved the classics. I loved The Little Princess, Black Beauty; a bunch of things I would never dream of reading now because they’re incredibly boring. Perhaps that’s because of my school library. My parents couldn’t afford to buy books, all of what I was accessing was in the context of Meyersdal Primary School’s library. All of that was old books which had zero relevance to my actual life. But in a sense, I treated them all as fantasy and they didn’t have to be relevant to my life actually.

I was a voracious reader, I was one of those kids that became a library monitor. I read everything I could get my hands on. I was a big fan of Roald Dahl, I loved Jacqueline Wilson who is a British author for kids. She writes the most wonderfully empowering stories about young women and girls friendships. That resonated with me then and it resonates with me now. It’s part of the stories that I write, which is very much around girl friendships.

It’s interesting how you said your earliest memories of writing. In those days, did you see yourself as a writer?

Never, even though I wrote throughout my childhood. In my teen years, my parents put the family computer into my room so I could write throughout the night. I didn’t sleep: I wrote plays, poetry, all sorts of things. But I never considered myself a writer even after I’d been published until fairly recently, which is a weird kind of cognitive dissonance.

There’s so much that you put on the word ‘writer’. It feels like it’s this big impossible thing that you couldn’t possibly be. It felt too much like calling yourself an artist, which is pretentious almost. That’s also what makes people afraid of reading and writing is the pretensions we put on to it. We forget that for most of history reading and writing never existed, but we always told stories. We always were interested in human experience. That wasn’t just something for the rich or the elite or the intellectual.

Our grandmothers or parents told us our first stories and they don’t fit into this elite bracket. But their stories were still entertaining, right?

Yes. Entertaining, educational, philosophical. I feel I missed out on in my childhood: my grandmothers never told me any stories. They believed there would be no future in those kinds of thoughts or concepts or ideas. They wanted me to read and speak English. They came from that mindset that this was not valuable, not what people who want to succeed and be exceptional do. I find it sad. It still has a huge impact on my life, I still don’t know the stories of my family.

Your books are so different from that. They are Afrocentric: in the setting, the characters, and how you delve into African mythology. Why do you think it’s important for children to see themselves in the books they read?

I never saw myself in any of the books I read but that didn’t prevent me from reading or enjoying them. But I do think there’s something around being able to imagine yourself and a different reality for yourself. Children who are not children of colour have always been able to do that. That’s why I like the idea of writing fantasy and putting black children in it. There are books with black characters but a lot of it is around poverty, around apartheid. None of it is about having fun and chasing the monsters or whatever.

I like the idea also of putting African mythology into the stories because it gives the stories that kids have heard from their grandmothers or mothers a place outside the home, which gives them credibility. It makes those stories matter.

I grew up with this idea that characters in books had to be blond with blue eyes and live in England or America. It’s only now that I’m older, that I get to read children’s books and Young Adult (YA) fiction that I can imagine myself in stories. Why did you decide to write children’s books particularly?

I read and write a lot of YA too, that’s my favourite type of story. I do read literary fiction, but more as a break from YA rather than the other way around.

The reason I wrote this series was more because there was a publisher who wanted to publish a series for this age. It wasn’t intentional. I had a relationship with Cover2Cover Books because I wrote for their website as part of FunDza Literacy Trust. FunDza’s whole thing is creating an online library of thousands of really well-written South African stories for South African children available for free. They’d discovered that there’s this gap for 9-12-year-olds. At the time when I started writing this six years ago, I couldn’t find a single other South African fantasy book for 9-12-year-olds.

When you think of Roald Dahl, books like the Witches should not be child-friendly but that was written for 9-12 year olds. I took my cue from that and thought clearly this doesn’t have to be dumbed down or tame and I could do this. That’s kind of when it started.

I think Animal Farm was at one stage a children’s book. It’s difficult to imagine that.

There are different levels that we read books. You can read some works as a child and interpret them a certain way and when you read them as an adult there’s a whole different lens you read with. You get a whole different experience. That, I think, is exciting. There’s a lot of women who tell me, ‘these are such feminist stories.’ I’m like, ‘yes because I am a feminist’ but kids aren’t reading it like that at all. I like that multi-faceted element of children’s books.

What have the reactions to your books been from children?

I love doing school visits because kids are very honest. Every time I do a school visit there’s always some sweet child asking me why there’s people being mean in my books. My first book opens with the main character Nom being bullied by some other girls. Some child’s always traumatised by this.

The other questions are much more about the writing process. They’re interested in how long it takes, and how you find someone that will publish the book. I think it’s because it’s not only that there aren’t black characters that they get to see themselves in but there also aren’t many black creators of art. JK Rowling or Roald Dahl don’t look like them.

At some point everyone asks, ‘so you say you’re South African but what school did you go to?’ When I say Meyersdal Primary they’re like, ‘what are you talking about that’s 10 minutes away from here’. That was 50 times more interesting for them: that someone who grew up 10 minutes away from them could write and publish a book that they could read.

It all goes back to being a writer seems like a big and scary thing.

We have this weird culture where you have to have permission to be an artist, a writer and a reader. Sometimes I feel like my work is just giving kids permission to do or be something else.

You mentioned earlier that you’re a feminist. What’s it like being a feminist writer and writing empowerment into your books?

Being a woman has never been easy, but in 2019 it feels like there is a special assault on women. There’s no safe place for women, especially in South Africa. I have really enjoyed writing girls who have a bit more agency than that, that sometimes put themselves into dangerous situations out of choice. They don’t know it’s dangerous but they want to be brave, and it can have a happy ending as compared to the ending we expect. It feels very freeing for me to write girls who have power and magic.

I like that Nom is one kind of girl but Zuleikha, the Muslim ghost, is a different girl entirely. There’s characters in the new books who are also different kinds of girls and women entirely. There are girly girls and those who are quite sassy, the only thing they all have in common is that they are all brave. That’s the kind of feminism I want to read and write about, women and girls who all just brave.

Interview edited for length and clarity.

Bontle Senne will launch Night of The Red Moon, the fourth book in her Shadow Chasers series, on 1 March at Exclusive Books in Rosebank at 6 pm, and 2 March at Bridge Books in Newtown at 11 am.