She is a woman cloaked in fable and intrigue but Leila Khaled, above all, embodies a history of resistance. And to the many, many young people who first encounter her in books, she represents the enduring hope for “home” as a sanctuary from oppression. But she is above all, a living being. MUHAMMED ISMAIL BULBULIA reflects on what Leila Khaled means to him.

Leila Khaled is watching, with catatonic calm, the way a tigress in a cage might watch an observer, a speaker on some stage in Laudium spill out the details of her life story in front of a crowded hall. It is 2015. She is 70 years old. She is sitting in this hall, hundreds of miles away from a home she cannot return to, immersed amongst people that swear to be committed to her cause: people who cry for Palestine, people who take selfies for Palestine, people who will even boycott their very favourite premium coconut milk for Palestine! The introduction tapers to an end. Leila takes centre stage to thunderous applause and begins her address; her voice rough like the cigar smoke of which she is so fond. Most of the people attending are here simply to say they were. I am here to meet my heroine.

For me, it began, of course, with the photograph. The first I learnt of Leila Khaled was from that monochrome photograph, nestled in a history book entitled “Days That Shook The Worldâ€.

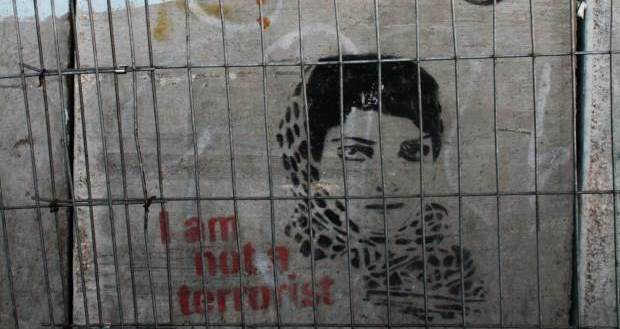

The photograph that enshrined her in collective consciousness and birthed names that would cling to her like an insistent lover for the rest of her days: Terrorist. Freedom fighter. Hijacker. Sex symbol. Femme fatale of the Fedayeen. Leila goddamn Khaled.

Leila, who holsters an AK-47 with the coolness of a Tarantino character and wears rings made from grenade pins wrapped around bullets. She is delicate and she is powerful. She is the beach city and the hurricane. Standing there with her Mona Lisa smirk, the storm in the scarf, instilling the impression that if you remain in her orbit long enough you, too, just may be able to do something crazy and heroic for the things you love.

In that aura of happy defiance lies the personification of every hardship of her people: every mother that died in childbirth at a checkpoint, every daughter that lost a childhood, every wife that lost a husband to perpetual purgatory – they are there, present in the gleam behind that smile, daring you to complain about the weather or the WiFi. That particular smile was not to last, however. Fame was an irritation Leila neither craved nor coveted; she refused to walk around with the face of an icon.

Six cosmetic operations later, she was just unrecognisable enough to do it all again. So she did.

The Leila of today is a lifetime away. She is slower, smarter, gentler, disinclined to blowing up any aircraft. “What purpose would it serve? People know some of our pain now. We have some of the world’s attention where before we had none,†she replies to a question from the crowd. She has realised that a woman can “be a freedom fighter and she can fall in love, and be loved, and she can be married and have children and be a mother.†She has reaped the fruits of allowing herself to sow love amongst groves of deep hate. She is, in a word, old.

When I see her now I see Muhammad Ali, the glorious afterglow of a fighter with not enough fight in their body to match the light in their soul. Shaken but not beaten, still standing against the anticipation of the final KO. In my mind’s eye I picture them old timey cartoon style, caricatures in rickety chairs, smiling over a cigarette and reminiscing over times they made world shake before the world shook them. Yet, what hope is there for a truly free Palestine in her lifetime? Perhaps it is better to die a Hani than a Mandela; perhaps death on the cusp of a dreamed utopia is better than a rainbow damnation.

Revolutionaries should live fast, die young, leave a pretty corpse and be buried in struggle songs and quotes out-of-context and murals on walls in dying cities and post-postmodern analyses of what they said, did or liked. Sometimes I wonder whether a Biko still living would have borne the brunt of ‘94 with nothing more than a sad smile, or if a Gedleyihlekisa gunned down in glory in the prime of his MK days with umshini wakhe would have calcified him differently in our hearts. Nay, revolutionaries are so revered because the inevitable coup de grace came swiftly before the inevitable catastrofuck of trying to fix vestiges of problems they did not cause. What is the difference between the Lumumbas and the Mugabes, besides 20 odd years and bullets that found home? “You either die a hero or live long enough to see yourself become the villain.†Leila has been called both, yet even as she lifts yet another cigarette to puff away the remaining years, she has stuck stubbornly to her dreams of home, still willing to die for it just like so many of her people. Maybe for that, if nothing else, she is a hero.

This is part of a special series called Apartheid 2.0, which The Daily Vox is running this month in partnership with Al Jazeera’s Palestine Remix.