Deon Maas packed up his whole life and moved to Berlin with his wife and four dogs to seek new adventures. There, he walks dogs and writes books. His latest offering is called Witboy In Berlin, and is brimming with his musings about the anarchists, vegans, musicians and artists he has encountered in Berlin. SHAAZIA EBRAHIM said down with the colourful author to speak politics, identity, and belonging.

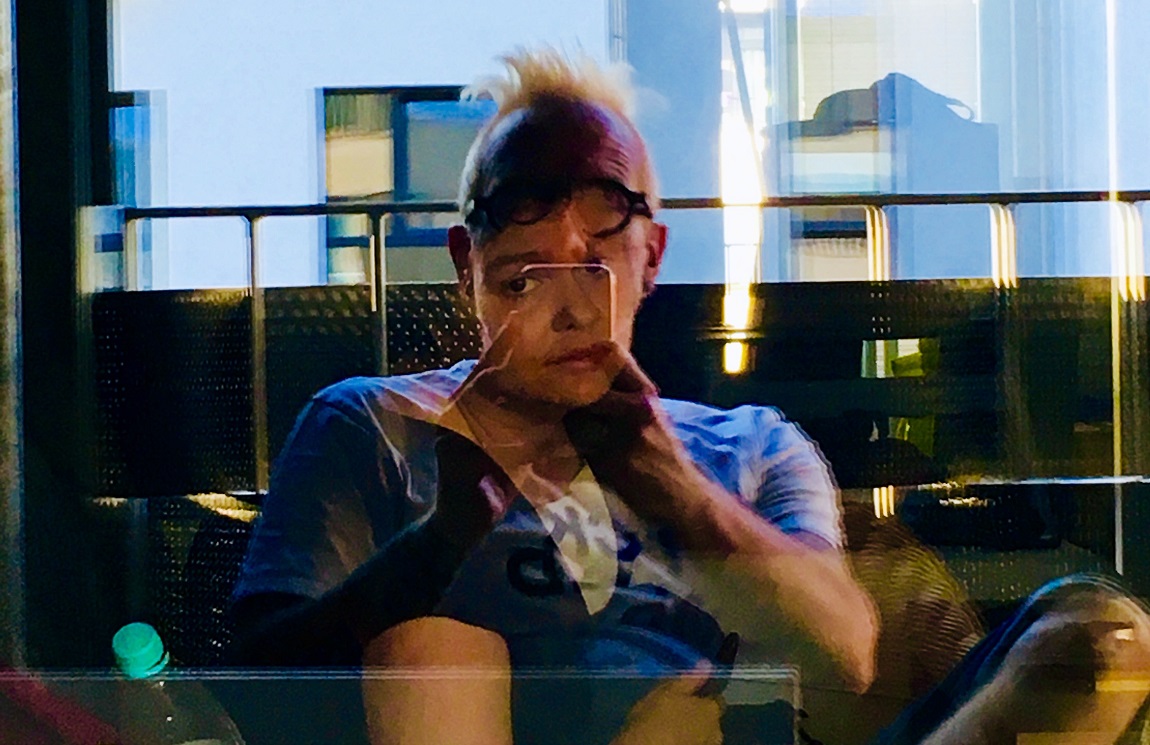

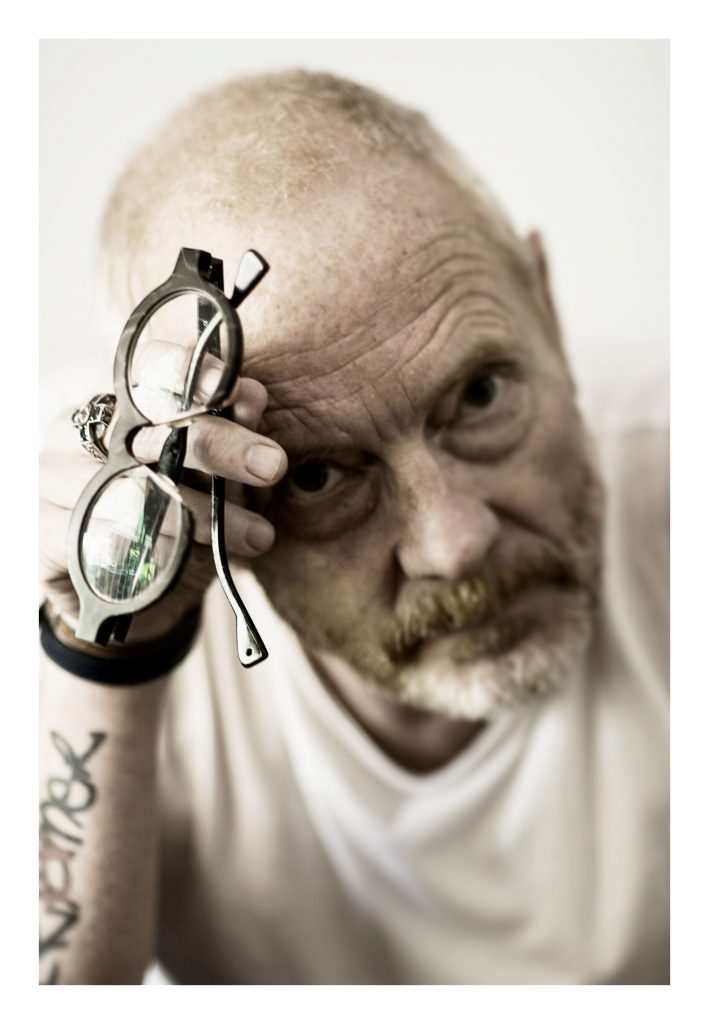

I met with the author in a quirky little coffee shop in Melville, Johannesburg. Maas was in the country to promote his new book Witboy In Berlin. Having never seen pictures of Maas before the interview, he was not quite what I was expecting of a middle-aged, Afrikaan-speaking white man. With his tattoos and piercings and round frames, he was not out of place in the hipster heartland of Melville.

Having worked in the creative industry for such a long time, I should have known Maas wouldn’t be suited up. He has also co-produced television series Jam Sandwich and Fortuinsoekers in South Africa and the reality show Gulder Ultimate Search in Nigeria. Maas has also written a book called Witboy In Africa: Diary Of A Troublemaker.

While his earlier book was filled with drugs and alcohol and women, Maas says, Witboy In Berlin is quite different. “This is me being grown up and allowing myself to feel. Maybe because living in Berlin is making me all soft and squishy,” he said.

When his partner secured a top job in the fashion industry two years ago, Maas saw it as a good opportunity to journey yonder into the so-called First World. After a couple of visa hiccups, Maas finally moved to Berlin a year ago. There he is a dog walker (and author).

“I love being a dog walker, I have all this free time. It gives me time to think. I do all my planning while walking the dogs and I’m using the dogs as a way to explore Berlin,” he explained.

Maas is not in the least ashamed that he walks dogs. In his observations since moving to Berlin, he says South Africans are snobs who look down on blue collar work.

“In Berlin, there’s no looking forward to blue collar. Whether you’re a doctor or a plumber, you drink in the same pub. Nobody gives a shit,” he said. Given that professionals and blue collar workers live in the same buildings, Maas says he sees it as “a very socialist way of thinking” and a “comfortable way to live with your neighbours.”

In his book, Maas makes a lot of observations about the lifestyle in Berlin, German people, and even immigration. I asked him whether he feels a crisis of belonging being so far from the country he was born in.

“I think the word belong is very overrated. I’ve never felt like I belonged anywhere. Some of that has to do with me being white and living in Africa,” Maas said. As a white-skinned person in Berlin, people presume that he is European. But Maas is African too, he says.

“I’m too white to fit in South Africa and too African to fit in Europe,” he said. Despite his skin colour, Maas says the context he grew up in gives him an Africanness in his thinking and outlook. “Your skin colour doesn’t determine your identity. There’s a certain rhythm in the chaos of Africa that gives you a freedom that you don’t encounter anywhere else in the world,” he said.

Maas says his roots don’t determine who he is. “I don’t identify with the Afrikaans culture, I have nothing in common with those people.That would make me a nationalist, that I have to vote for the Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB) or something. But I also have nothing in common with some Germans. That’s where the global citizen thing comes into it, people whose identity is not having an identity but a belief system. That’s really where the world is at the moment, it’s a split between the nationalists and the global citizens,” Maas said.

As a global citizen, belonging means something different to Maas. “The idea of belonging, as I’ve gotten older, has become rather a question of feeling comfortable with myself: both adapting to my environment but also allowing my environment to adapt to me. In other words: finding a little space where you can do your own thing but also being respectful of other people,” he said.

The politics in South Africa have become so convoluted, so stuck in identity politics and race, Maas says.

Maas is as anti-establishment as they come. He says although he doesn’t eat meat, he prefers not to call himself a vegetarian. “The moment you put yourself in a box, or other people put you in a box there’s certain restrictions. Then you have to buy into someone else’s philosophy and you start compromising your own,” he said. It’s no surprise, then, that he is friends with anarchists in Berlin.

“I love my anarchist friends because I share a lot of their political beliefs. But at the same time, I would love to see them live in Soweto for a couple of months, being exposed to the realities of Africa to see how strong this anarchist belief is and whether they can adapt their very European understanding of this philosophy into a workable solution in Africa,” Maas said.

Like with communism and socialism, archist doctrines are pure but they don’t work because they eliminate human emotion, he says. “That’s what fucks everything up at the end of the day: humans,” Maas said.

“The thing I find incredible after Berlin is that I don’t know where to live after Berlin because it’s such a free-thinking, anything-goes kind of a setup. It’s going to be very difficult to find another city where you are allowed to be this flexible,” Maas said.

Aside from his friends and family, there’s not much Maas misses about home. This is partly because he’s traveled so frequently and is quite used to making do with what he has. But he figured out one thing he does miss.

“I miss peeing in the garden. In Berlin, I don’t have a garden,” Maas said

Published by Jonathan Ball Publishers, Witboy in Berlin is available at most good bookstores for R260. Also available in Afrikaans.