By Terri Maggott

On August 2 2019, numerous reports of violent femicides sent shockwaves through the nation. In the same week, the news of brutal killings of foreign nationals in Pretoria and Johannesburg flooded the media. Two types of violence raged side by side – xenophobia and misogyny. The high levels of violence are unsurprising in the most unequal country in the world.

In a webinar, hosted by the University of the Witwatersrand’s Gender Equity Office, Anda Dungulu, leader of the Black Womxn Caucus, aptly captured this reality by pointing out that, “where there is misogyny, there is racism; where there is xenophobia, there is misogyny. Violence is intersectional.” If life for South African women, particularly black, poor women is difficult – even with access to social protections such as healthcare and education (although limited) – imagine what life is like for undocumented, refugee, and asylum-seeking women migrants.

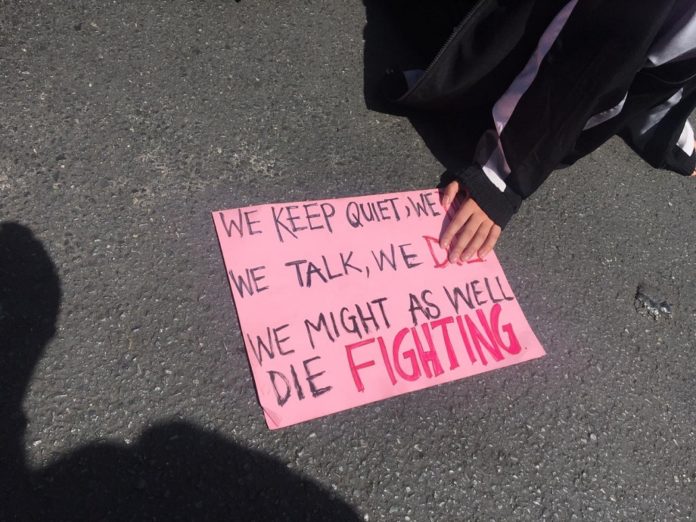

The fight against gender-based violence (GBV) in South Africa has gained momentum in recent years since the outcry against the infamous femicides of Anene Booysen in 1999; Uyinene Mrwetyana in 2019; and Tshegofatso Pule in June 2020. These “mega cases” – as author Nechama Brodie called them in her 2020 book, Femicide in South Africa – have received much public attention. But in the shadows of society, where undocumented or irregular migrants are often forced to forge out their existence, is a more complex reality for women.

The process of becoming legal is very difficult for undocumented migrants, refugees, and asylum-seekers, owing to a major processing backlog at the Department of Home Affairs (DHA), as well as to South Africa’s long history of anti-immigration sentiments. During apartheid and since 1994, the South African state has viewed immigration as an economic and security threat. The African National Congress (ANC) government has maintained this stance, treating migration as a problem of security and not as an opportunity for development and solidarity-building. Despite this, South Africa is still a preferred destination for many migrants in the region and the continent. According to the 2011 Census, South Africa was host to 2.2. million migrants. The Census also reported that 75% of migrants in South Africa were from Africa, and 68% were from Southern African Development Community (SADC) member states.

Women migrate for several reasons: to access education and economic opportunities, and to escape oppressive economic and gender regimes in their home countries, which deny women basic rights such as access to schooling and property ownership. During their cross-country journeys along Africa’s various migrant routes, women and girls are subject to specific types of sexual abuse and exploitation. Both men and women are potential victims but women are particularly vulnerable to sex trafficking, comprising 80% of victims globally in 2019. The rate of trafficking in East and southern Africa would likely increase under COVID-19 as government and police protection became increasingly unavailable to migrants during lockdowns.

When migrants arrive in South Africa, they encounter everyday xenophobia, or Afrophobia – since black migrants are the main targets of attack when compared to their European and Asian counterparts. Coupled with high levels of GBV, migrant women face a “triple oppression” of xenophobia, racism, and misogyny. The number of women migrants in South Africa quadrupled from 2000 to 2017, from 400,000 to 1.8 million – 44% of the approximately 4, 1 million migrants in South Africa. Women are increasingly migrating independently of their husbands and families, and are making independent choices about where, when, and how to migrate.

During COVID-19, the sudden shrinking of the global economy has strained the already-precarious situations of undocumented women migrants. Reuters reported that women living in dilapidated buildings in Central Johannesburg are forced to choose between paying rent and buying food. Just as other wives and single mothers, migrant women are often responsible for feeding their families, and since non-South Africans have been effectively excluded from the South African government’s COVID-19 relief funds and food programmes, they face serious challenges in meeting their families’ most basic needs. Domestic work and other informal trade are the primary occupations for many women migrants in South Africa, and the lockdown has meant an interruption in this source of vital income. Beyond COVID-19, reporting incidents of rape, sexual harassment, and GBV is often difficult for migrant women because of the xenophobic attitudes of local police and healthcare workers.

With little support from the government, women migrants have established their own networks of support, which are vital for their survival, as Oluwakemi Oyewole Kimi, a Nigerian migrant and feminist activist in Serbia, noted in a webinar on 8 July 2020, titled, “COVID-19: Migrant women resisting increased control, abuse and inequality”. Without these networks, migrant women are either excluded from important information and resource sharing or, where they are married, are under the custodianship of their husbands, who they must trust are making the best decisions for their families.

African feminists have long argued that change is attainable only when society’s most vulnerable members are protected. Therefore, the fight against patriarchy in South Africa must acknowledge and incorporate women migrants into the broader conversation. Some of the similarities between South Africans and migrants – such as high unemployment, and issues of access to adequate healthcare – are common ground from which to forge a meaningful, Pan-African resistance against xenophobia and sexism. To begin to dismantle divides between South Africans and migrants, women activist groups in the country must extend an open hand of solidarity to women migrant networks and include them in the fight against GBV and xenophobia.

Terri Maggott is a Research Coordinator at the University of Johannesburg’s Institute for Pan-African Thought and Conversation (IPATC).