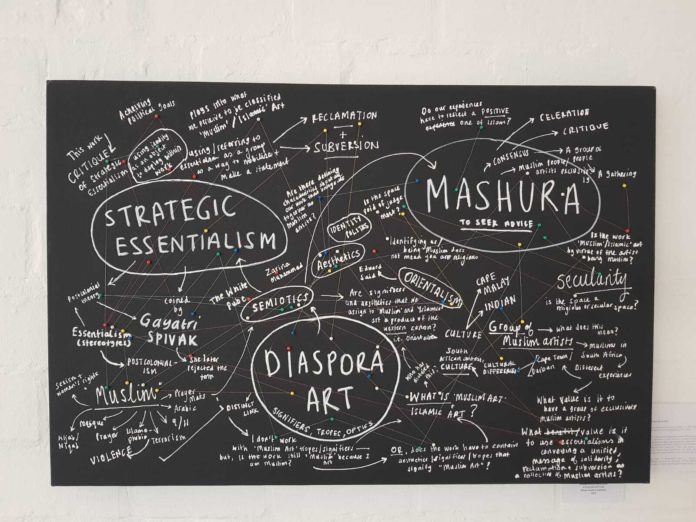

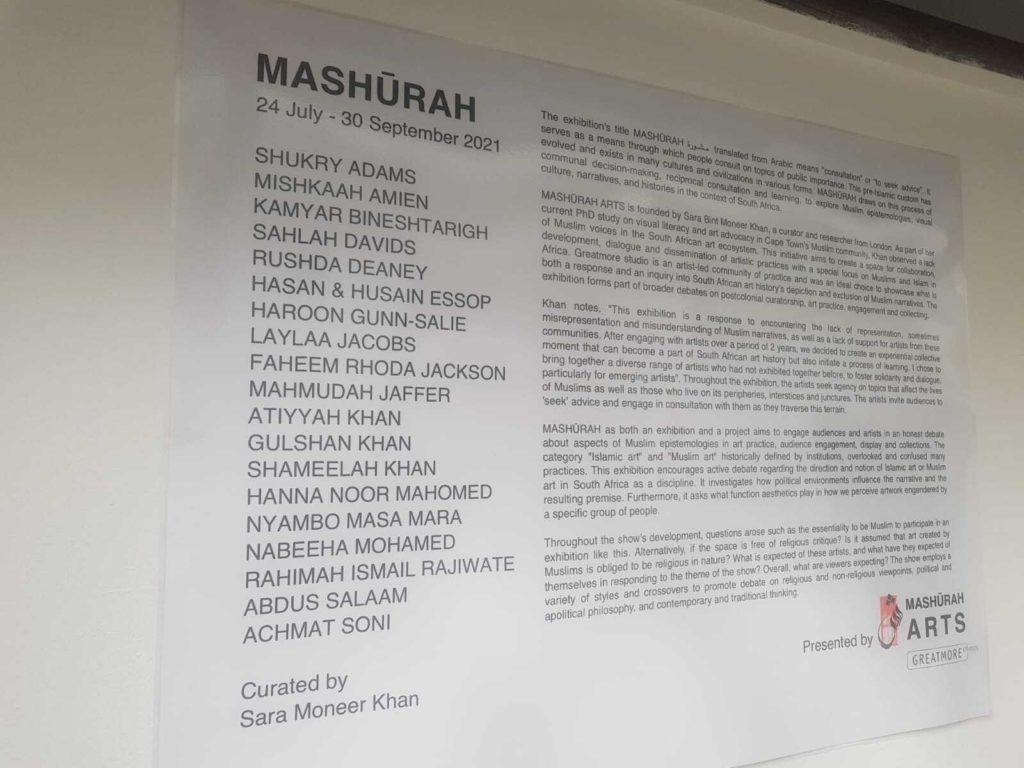

MASH?RAH ARTS is a new initiative that aims to amplify Muslim voices in the South African art scene. Their first exhibition is titled MASH?RAH. Translated from Arabic MASH?RAH means “consultation” or “to seek advice”. The exhibition is on view until September 30 at Greatmore Studios, Cape Town, South Africa. The Daily Vox visited the exhibit.

Related

How Dario Manjate Creates Green Art

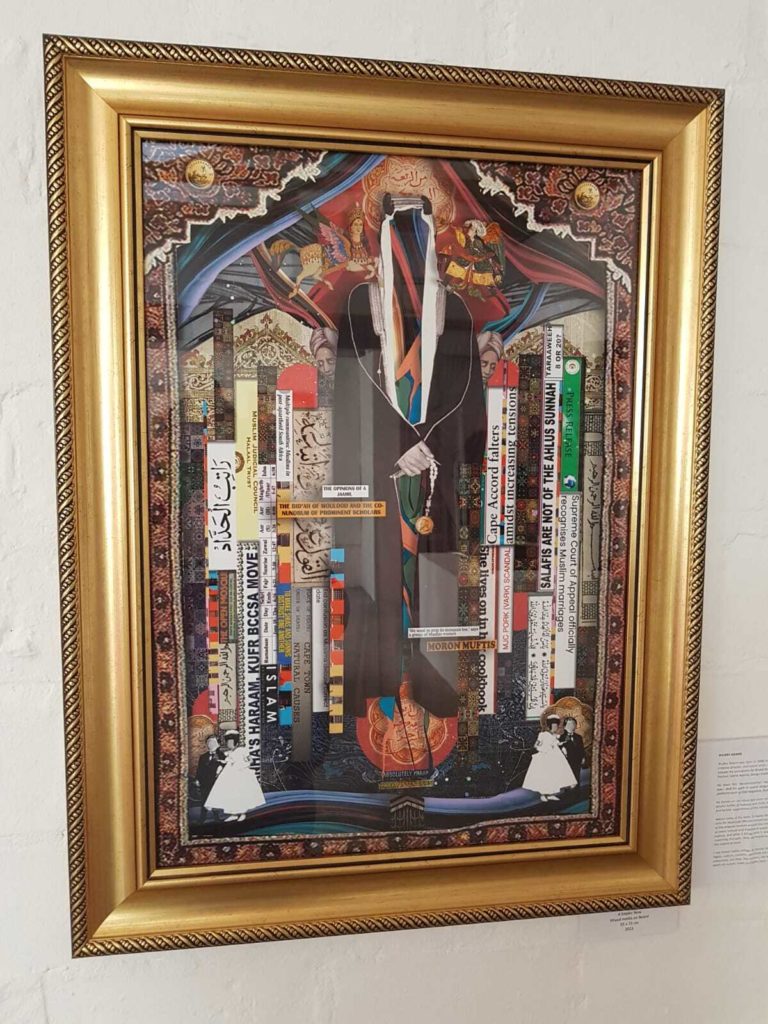

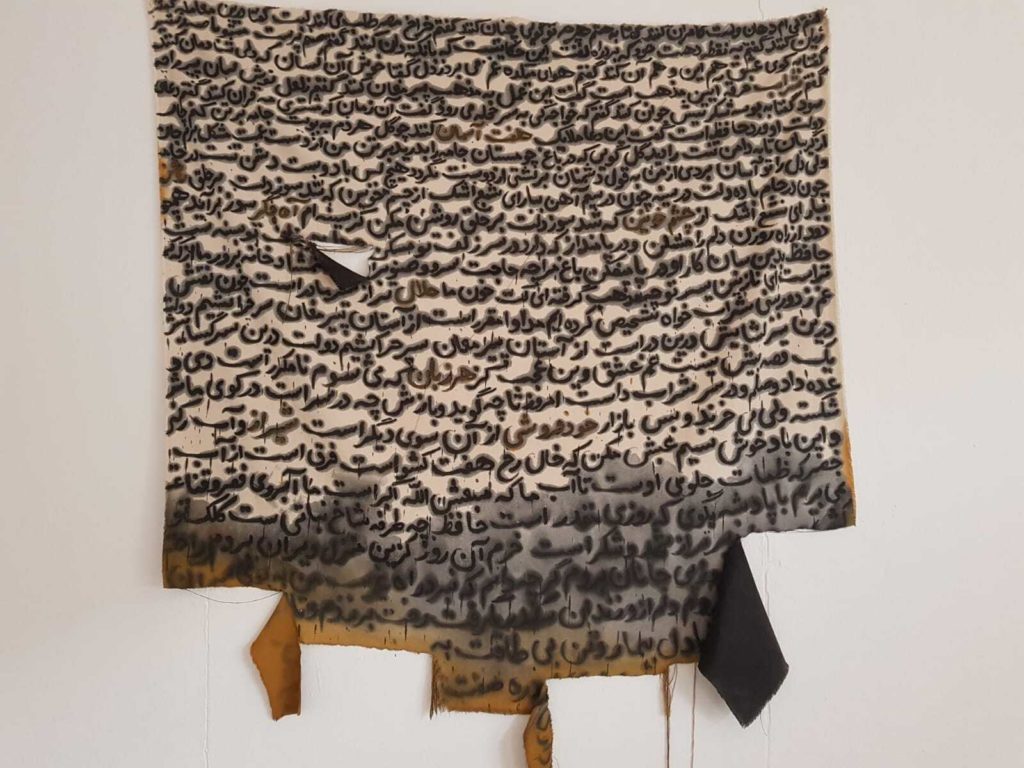

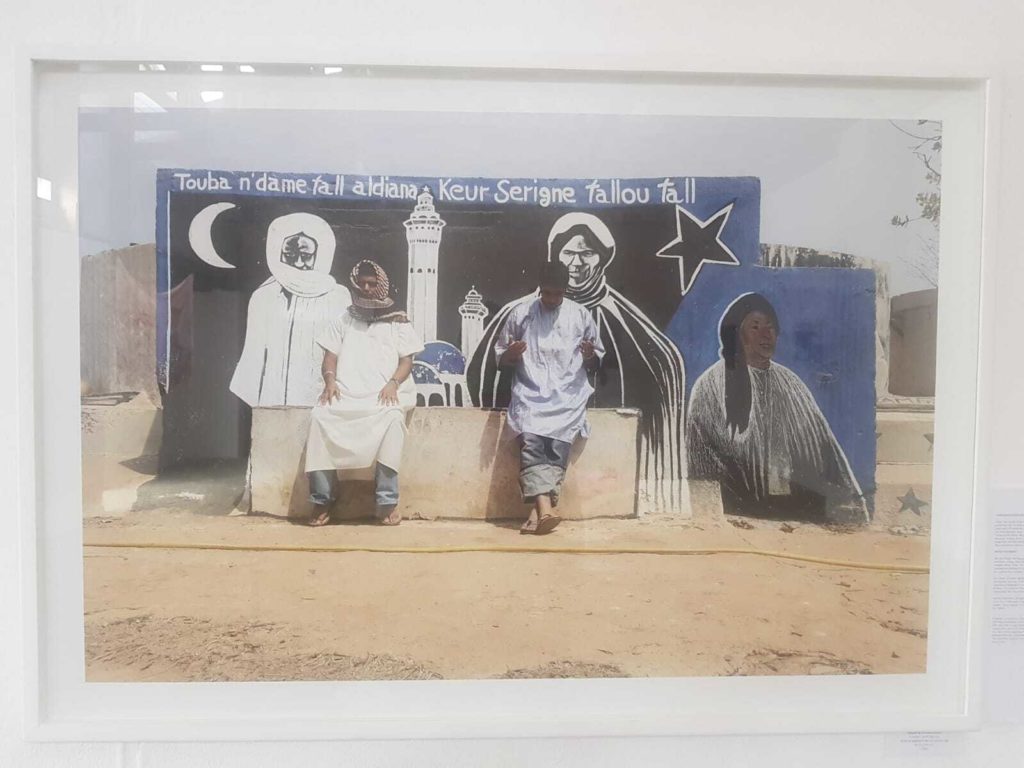

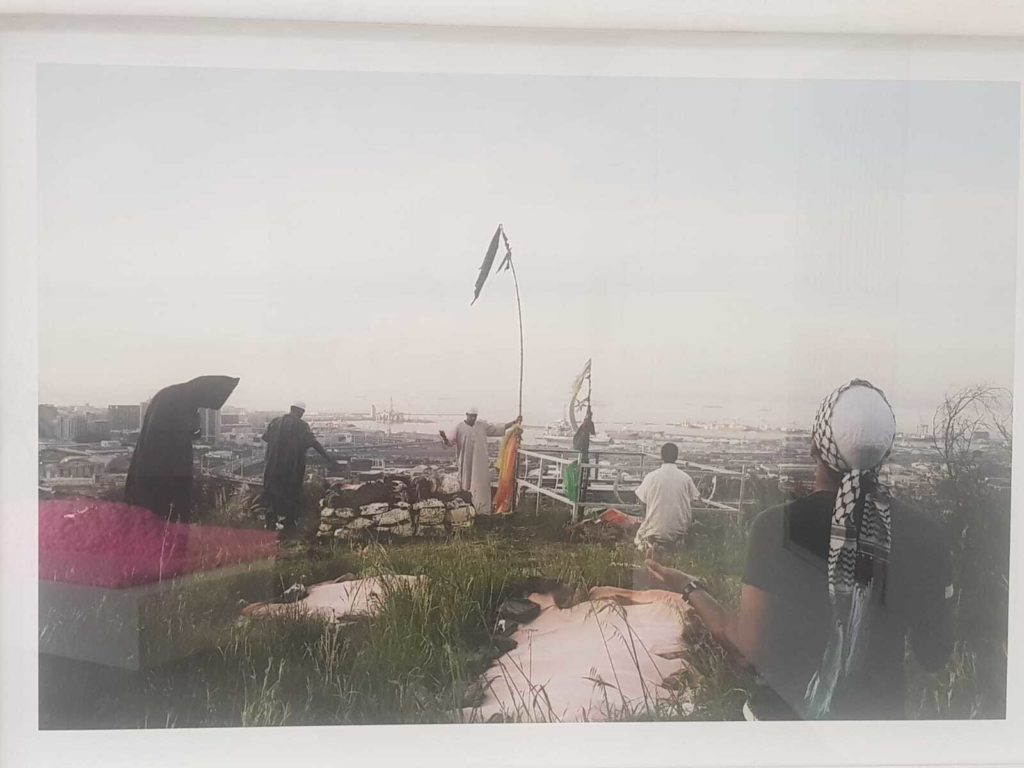

The exhibit is small and intimate, and occupies one room at the studios. The works are an eclectic mix of pieces that makes you want to get online and research everything immediately. It is an incendiary expression of colours and mediums from black and white imagery to mixed-media installations.

The founder of MASH?RAH ARTS, Sara Bint Moneer Khan is a researcher and curator from London. While doing her current PhD study on visual literacy and art advocacy in Cape Town’s Muslim community, Khan noticed a lack of Muslim voices in the South African art world.

Over two years, Khan brought together a diverse range of artists. The artists’ work are commentaries on their lives as Muslims intersecting politics and everyday life.

As varied as the art is, it is not distracting in any way. The bold colours from a photograph by Gulshan Khan catches your eye as soon as you walk into the exhibit.

Khan is a photojournalist based in Johannesburg. Her work focuses on stories related to social justice, identity and human rights. Girl on Carousel forms part of The things we carry with us (2017); an ongoing documentation of South African Muslims, especially women. Communities like these have limited visual documentation, and were less visible because of Apartheid and colonial erasure, Khan explained in her artist commentary at the exhibit.

The piece is striking and just by looking at it, it evoked “unadulterated joy”. It is universally relatable seeing the joy on the child’s face clearly, with the background blurred. Nothing else but enjoyment exists in that moment captured,with a part of her identity clearly visible.

Haroon Gunn-Salie’s piece, Amongst Men depicted the funeral of Imam Haron. Imam Haron was a Muslim cleric, and South African apartheid struggle hero. He was assassinated in September 1969, after 123 days of solitary confinement and daily interrogations about his involvement against the apartheid struggle.

“This work memorialises the impact he made.The image documents the moment just before the bier gets lowered into the ground. I erased all the people, so you only see the kufiyas. It is like the Apartheid government that assassinated and dehumanised Imam Haron,” Gunn-Salie told the Daily Vox.

Across the room Mishkaah Amien’s three violins play a silent movement that pulls you toward it. Amien created Ghost notes using laser cut plywood, black acrylic and thread. There was a deliberate choice in creating these facsimile violins and calling them ghosts.

Related

In his own words: Thomas Gordon and bringing classical music to the stage

Amien was inspired by her great-grandmother, Janap Daniels, with whom she connected with through their shared passion for the performing arts. Daniels was born in 1918 in District Six, Cape Town. She had to work as a dressmaker to support her family. Later she worked as a seamstress for the Artscape theatre, developing a love for the arts and classical music. (Amien is a member of the Cape Town Philharmonic Youth Orchestra as a violinist) While Daniels created the majestic costumes for the performances, due to the segregationist laws of Apartheid, she was never allowed to watch any of them.

Ghost Notes refers to the denial of experiencing the performances at the Artscape, and the generational trauma Amien experiences performing there in the present day. The violin’s hollow look is a metaphor for Daniel’s experience; creating beauty but not being part of it. Like the note playing faintly; almost as if it didn’t exist.

Related

Book Review: District Six – memories, thoughts and images

Speaking to The Daily Vox creative and filmmaker Shameelah Khan said her film, The Wedding Day was inspired by looking at the intersections of motherhood and memory. The film was part of her masters studies. Khan digitised her parents’ wedding video during the lockdown restrictions. She said she wanted to look at reclaiming voices and recutting the archive, to re-examine memories in a different way.

“I’m inspired by my own heritage, culture and my relationship with my mother. Intergenerational stories that are influenced by memory is where I draw from,” Khan said.

All the works deserve individual reviews and analysis. The best advice would be to go and view them for yourself. I circled the room multiple times to take it all in. The artists may be Muslim, but their works,commentary, and inspiration transcend their religious affiliation. They do this by weaving it into narratives and embracing it. The exhibit is a microcosm of an oft misunderstood community, which are more than the one thing we define them by.

With that being said, viewing the exhibition space, one can’t help but wish there were more works on display. Despite its size it leaves a lasting impression. Proving that visibility is important no matter how small. Art exists to make us think deeply about the world around us.

MASH?RAH goes above its meaning by highlighting how the artists have experienced the world, and perceived it with artistic expression. Visiting exhibits like these are important to create awareness, dialogues and to constantly problematise the world around us, and the people who inhabit it.

Read more:

Jeffrey Oarasib on affirming Khoi identity through art