It was 2012 in the Cape Flats in Mfuleni. Demanding better police services in Khayelitsha, community activists Angy Peter and Isaac Mbadu were raising their young family. However, the tables turned when the Khayelitsha Commission started its hearings and Peter found herself on trial for necklacing young neighbourhood rabble-rouser Rowan du Preez. The State alleged that, on his dying breath, du Preez confessed that Peter and Mbadu set the tyre alight around his neck. But what is the truth? Was Peter a framed by the police for a crime she didn’t commit, or is she a murderer?

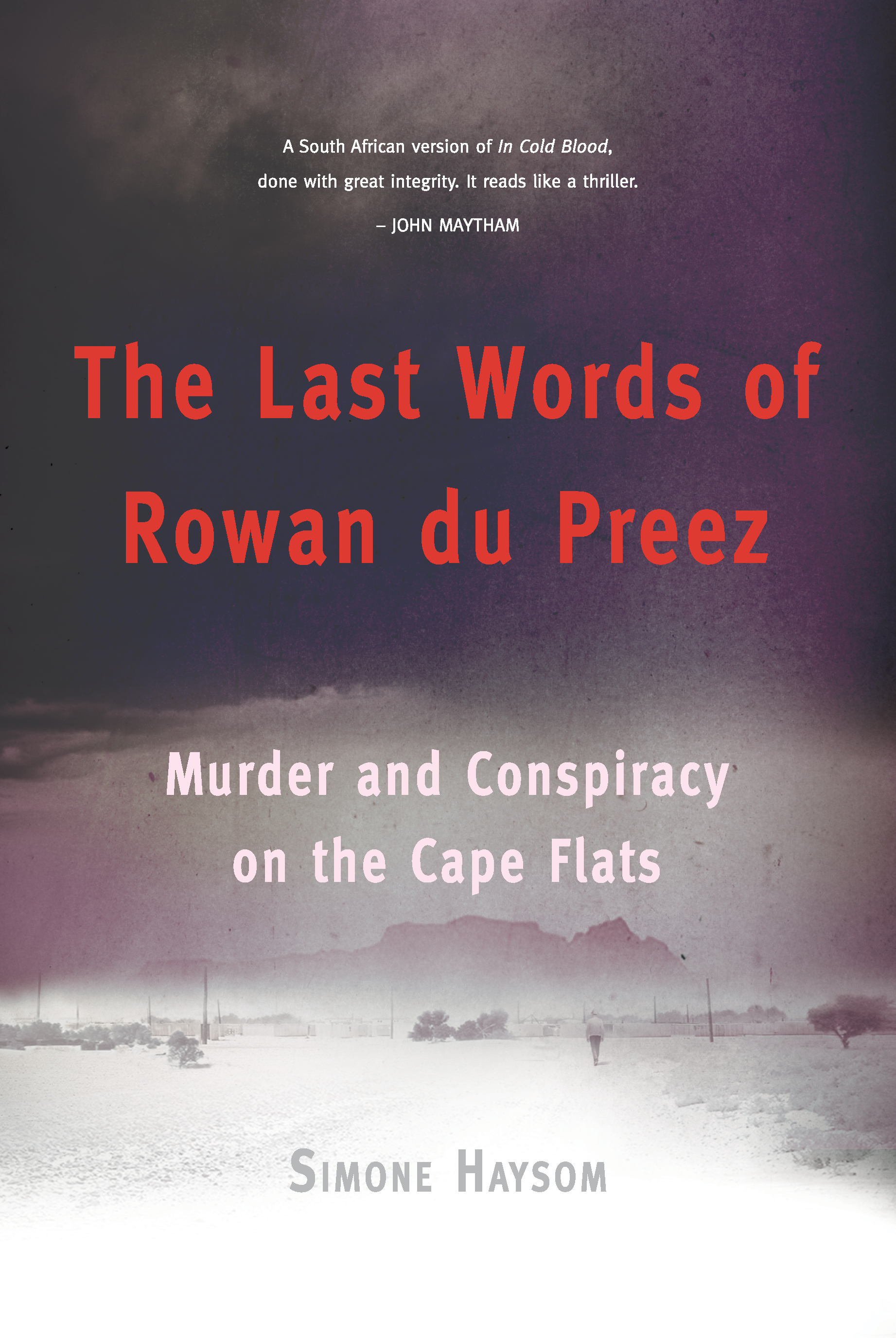

Author and crime researcher Simone Haysom captures the case and the search for truth in her gritty true crime book The Last Words of Rowan du Preez.

Although Du Preez’s case was not a big, sensational trial, it was an important one. It didn’t really get much coverage outside Cape Town. Haysom wanted to find a small story that could speak to much broader issues.

“It was a fascinating trial and was connected to really important questions about our democracy and our country. Symbolically it brought together different issues of vigilante justice, feelings towards criminals like Rowan du Preez, activism and what role this plays in parts of the city which are in many respects very lawless. At the core of it was this question: can we trust the police to be telling the truth about what happened to this very vulnerable person? That’s a meta-question about the role the police serve in our society,” Haysom says in an interview with The Daily Vox.

Haysom is interested in the truth and who – which institutions – are equipped to uncover it. The police, she says, should be interested in truth.

“We don’t often think about them this way but one of the roles of the police is to uncover the truth. We tend to think of their role as making arrests and convictions but arrests and convictions are supposed to be based on investigations,” Haysom says. We often rely on the court to deliver justice based on truth, but there are flaws with this too.

“Realistically, what courts do is decide on two arguments about what the truth is so there’s already a lot of things excluded from what the truth could be or perspectives on the issue. Their role is to come to a just position about which of those narratives is closest to the truth,” Haysom says.

But for ordinary people like du Preez and Peter, both of those systems are highly dysfunctional to the extent that we can’t have faith in them to deliver justice consistently. Both the police and the courts are deeply flawed mechanisms for meting out justice.

“We’re quite aware of the problems with the police because they manifest all the time. With the justice system, we’ve had quite a lot of coverage about the problems with the National Prosecuting Authority but the higher courts function quite effectively. But the issues that affect most people’s lives are decided at a Magistrates Court, maybe a High Court. They suffer from the same problems that a police station suffers from,” Haysom says.

“You can’t have people buy into society if they constantly engage with institutions that have no legitimacy,” she adds.

In Cape Town particularly, while Haysom can’t say they’re completely ineffective, police are operating in environments where they are under-resourced and under corruption exacerbated by the large drug economies and amongst the elites. Many communities in Cape Town fall within the top 10 precincts for murder. Haysom’s findings were bleak.

Nyanga, SA’s Murder Capital, Still Only Has 1 Police Station

“All the accountability mechanisms in the police are broken from most basic ones where people submit complaints to the police to the oversight that senior leadership is supposed to provide,” Haysom says.

South Africans with the power to hold these systems to account simply privatise their way out of them. They use private security, or they have insurance which negates the need for police, she says.

For Haysom, probing very deeply into the police corruption caused her nervousness. “If the police did have something to protect then that was a frightening prospect: Who would they be accountable to? Who would you go to if you were afraid that the police were persecuting you? That’s what makes police violence so frightening, they’re supposed to protect you,” she says.

Personally, Haysom did not feel like justice had been served in the case. Not for Peter and certainly not for du Preez.

“In this book, the victim is a young man that most people would have very little sympathy for in other circumstances: a man with albinism, a convicted criminal and rapist from Manenberg. He fitted every stereotype of someone who would be the most isolated and feared in Cape Town,” Haysom says. And yet he, like everybody else, deserves justice.

“It’s terrible the discourse that we have around criminals and the way our justice system works: men enter adulthood as fucked up by the patriarchy as everyone else. These very violent or criminal identities are often a form of self-protection,” she says. Rowan entered the criminal justice system at a very young age with no prospect of rehabilitation. In South Africa, we don’t take rehabilitation seriously as part of the mandate of correctional services.

“All we care about is punishment. The usual idea is that the more punishment we heap onto people in society, the less need we will have for punishment. All the evidence shows otherwise,” Haysom says.

Writing the book, Haysom had a lot of sympathy for Rowan. She wants people to understand that when you read a story about someone who has been killed in a vigilante incident, it’s a person who had a family, and a life that could have turned out very differently. “Rowan was as complex as anyone else,” she says

Likewise, Haysom empathised with Peter too. “Angy made an equally ‘bad victim’ by traditional standards. We like our victims humble and quiet, especially if they are women. And Angy was not quiet – she was furious about how the police acted, and what happened at her trial, and with her colleagues. And because of her anger, in addition to the injustice that accompanies being poor and black, she received extra contempt from any authority figure,” she says.

This book is important because it asks important questions about truth, justice, and our democracy.

Published by Jonathan Ball publishers, The Last Words of Rowan du Preez is available online and at most good bookstores for R 275.